Book

A pair of public health optimists weigh in post-pandemic

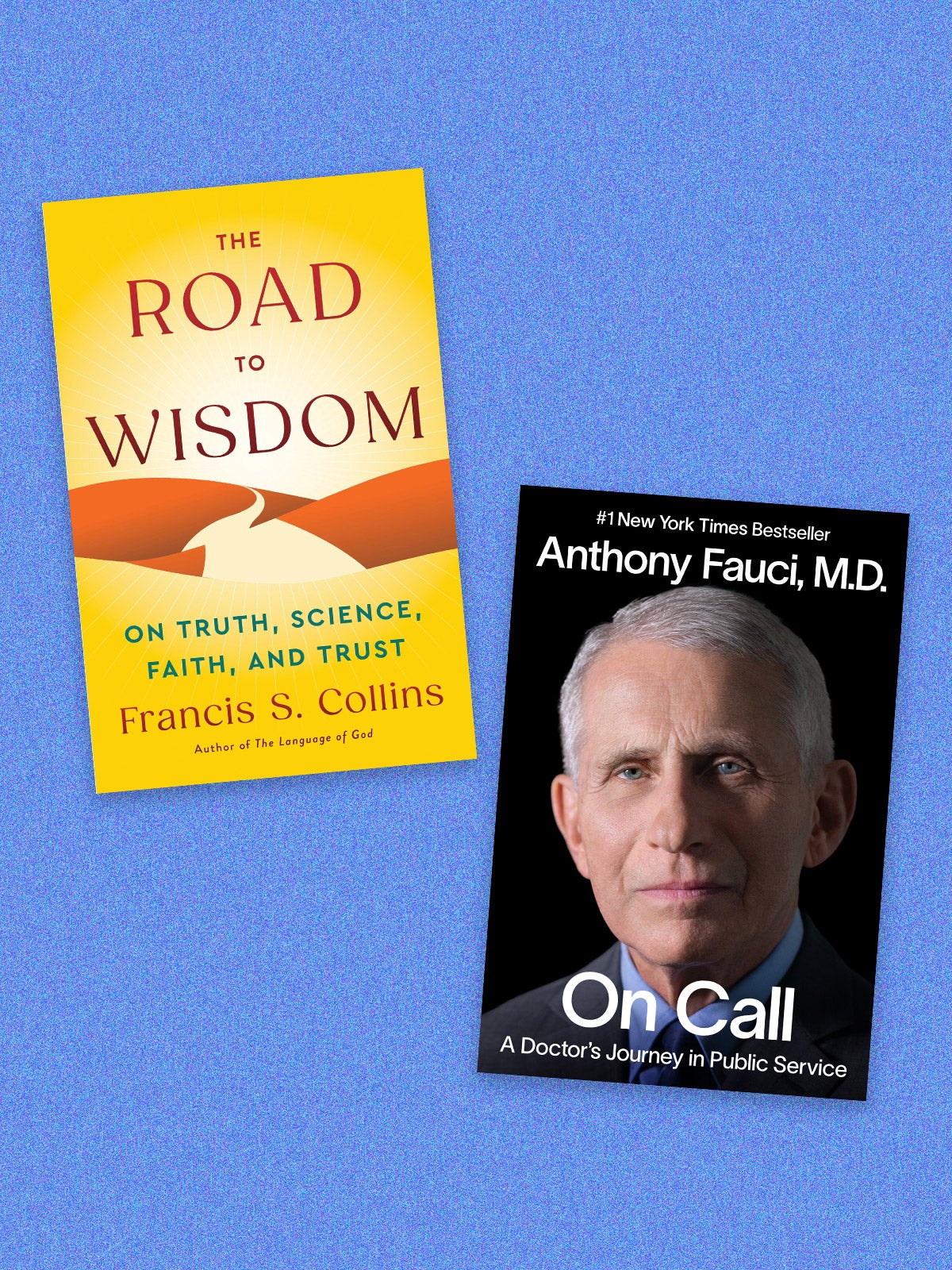

After intertwined careers in public health, Anthony Fauci and Francis S. Collins have both written books inspired by their experiences. Where they intersect most obviously is in dismay at the increasingly violent political and scientific divides plaguing the United States. Fauci documents how that polarization has imperiled both the nation’s health and his family’s safety. Collins provides a primer on how to address it.

The books are otherwise quite different. Fauci’s On Call: A Doctor’s Journey in Public Service is a straightforward, often engrossing autobiography with modest digressions into epidemiology and other scientific subjects. It covers his childhood, his medical training, and his career at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), where he retired in 2022 as the longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

In The Road to Wisdom: On Truth, Science, Faith, and Trust, Collins’s personal anecdotes serve primarily as case studies. Collins—who directed the Human Genome Project and, later, the NIH (where he was, for a time, Fauci’s boss)—combines philosophy, theology, sociology, and self-help in an effort to promote a more civil society.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

A straight-talking memoir

Fauci’s memoir, like its author, is plain-spoken and direct. The book can also be plodding, sometimes resembling an Academy Award acceptance speech brimming with praise for colleagues, mentors, and others. But what the book lacks in literary style, it makes up for in the power of its remarkable story, of a man who dedicated his life to public health despite sometimes steep personal costs.

The memoir begins with a November 2020 phone call informing Fauci of the astonishing efficacy of Pfizer’s new mRNA vaccine for COVID-19. The NIH Vaccine Research Center, which he had helped found, played a role in its rapid development.

Then Fauci flashes back to his middle-class upbringing as the son of first-generation Italian Americans in Brooklyn’s Bensonhurst neighborhood. He writes of his early career path, taking him first to medical school, during which he lost his mother to an aggressive cancer, and then, in 1968, to the NIH, where he made his reputation with research on autoinflammatory diseases.

Before Fauci became the revered and reviled face of the United States government’s COVID-19 response, he was most identified with his work on HIV/AIDS. On Call reveals just how deeply that crisis marked him. “I was trained for many years to be a healer, and during this period [of the 1980s] I was healing no one,” he writes. At NIAID, Fauci pressed successfully for more federal research money, spurred the development of a nationwide network to test new AIDS drugs, and helped HIV/AIDS patients secure access to experimental medications on a “parallel track” that complemented clinical trials. ACT UP cofounder Larry Kramer, a novelist and playwright who had defamed Fauci as a murderer and “incompetent idiot,” became a valued confidante, as did other activists. After the seemingly miraculous drug cocktails of the mid-1990s turned the tide against AIDS (at least for those who could afford the medication), Fauci spearheaded George W. Bush’s Presidential Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which supplies HIV/AIDS drugs and supports prevention measures in more than 50 countries.

Fauci’s obsession with AIDS helped cost him a brief first marriage and led to his current one, with a clinical nurse specialist, Christine Grady, who worked in the AIDS trenches with him. He lost his deputy director and close friend, James Carroll Hill, “someone whom I loved,” to the disease. He emerged, he suggests in the book, with both post-traumatic stress disorder and justifiable pride in his accomplishments, including his rapprochement with the AIDS activists who had once vilified him.

Fauci also takes us through public health battles against avian influenza, Zika, and bioterrorism, among others. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, he jumped in to treat patients at the NIH because, he writes, “I did not want my team to take a risk that I was not willing to take myself.”

Then the narrative returns to COVID-19. Though Fauci neither made nor enforced lockdown policies, his role as a cable television talking head made him a flashpoint for fear and rage about the disease. Fauci and his family started to get death threats, necessitating a security detail. As he fell from favor, the White House communications team curtailed Fauci’s television appearances, and President Donald J. Trump berated him over the phone.

Fauci tried to find common ground with opponents, among them Trump advisor Scott Atlas. The outreach failed. Atlas, a neuroradiologist who advocated less restrictive anti-COVID measures, “refused to give an inch,” Fauci writes.

Fauci revisits some of his own controversial statements without apology. He defends his early advice discouraging the use of masks to prevent COVID transmission. And he attributes his infamous testiness during a Congressional hearing on the source of the SARS-COV-2 virus to his questioners’ misstatements.

Toward a better future

Both Fauci and Collins describe themselves as optimists. While On Call is a chronicle of a life well-lived, Collins’s book is a cri de coeur that looks to the future. Its argument is, in essence, that truth, science, faith, and trust jointly lead to wisdom. In vouching for both the utility and accuracy of his evangelical Christianity, Collins (whose previous books include The Language of God and Belief) will likely repel some scientifically minded readers. He aims to strike a chord with his fellow evangelicals, many of whom distrust the scientific community.

An atheist in his youth, Collins notes that science cannot answer questions about life’s meaning. But his insistence on the validity—the truth value—of his religious beliefs is an awkward fit with his otherwise empirical attachment to provable hypotheses. “I have never encountered a situation where I found my scientific and spiritual worldviews to be in serious conflict,” he writes.

To Collins, dialogue with ideological adversaries is both possible and necessary. The Road to Wisdom is, in part, a response to the “significant pockets of public skepticism” that hampered adoption of COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Collins ruminates on how vaccine misinformation caused 230,000 needless deaths in the U.S., between June 2021 and April 2022, in what he calls a “tragic breakdown in our collective wisdom.”

This book reflects his effort to find a solution to that breakdown and to our growing social and political animosity. He draws on epistemology, the philosophical study of knowledge. In colloquial language, he distinguishes among necessary truths, firmly established facts, and zones of uncertainty and subjective opinion. He urges readers to counter the pernicious effects of the news media, social media, and politics by thinking critically about “the truth of a surprising new claim.” He calls on people to approach differences with “openness and generosity of spirit.” And he suggests that trust should be tied to perceptions of integrity, competence, humility, and aligned values.

The thrust of Collins’s argument is that we need to do a better job of listening to one another. “If our nation’s political system has lost much of its commitment to truth, compromise, and civility,” Collins argues, “it is up to us to turn that around.” It’s a worthy sentiment, even if remains an elusive goal.

Collins: Little, Brown; Fauci: Viking Penguin