Feature

Community fridges are helping neighbors nourish one another

This article was originally published by The Emancipator.

A curious sight is becoming more common in cities throughout America and abroad: refrigerators outside on the sidewalk, often adorned with colorful murals and posters inviting people to “take what you need, leave what you can.”

This is the mantra of the community fridge, a mutual aid project that brings neighbors together to find local solutions to the dual problems of food waste and food insecurity. Anyone can visit the fridge at any hour and take or leave food. Upkeep is done by a network of volunteers.

“We are not the police. We are not arbiters. We are just friends and community that are focused on helping folks have access to resources,” said Eric Von Haynes, co-founder of The Love Fridge in Chicago.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Mutual aid is a cooperative model of resource-sharing among communities, with no barriers to access. The idea is that everyone benefits when everyone helps however they can.

Megan Ramette, an organizer for the Allston-Brighton community fridge in Boston, goes to her fridge every Wednesday to pick up trash, wipe down surfaces, check expiration dates, and make sure food is properly labeled. Home cooking is welcomed at the fridge as long as it’s sealed and labeled with an ingredient list and a “best by” date.

“I love to cook a lot, so this was a really nice way for me to extend my kitchen table and my fridge to the community itself,” Ramette said. “It brings me a lot of joy. It’s a way for me to feel like I’m making a real impact in my community.”

As climate change makes summers hotter and extreme weather more common, community fridges are emerging as a way to reduce our carbon footprint—even with people going hungry, food waste accounts for 10 percent of global greenhouse emissions. The fridges also help neighbors share not just food, but other resources to make the community more climate resilient, such as water in the summer and mittens in the winter.

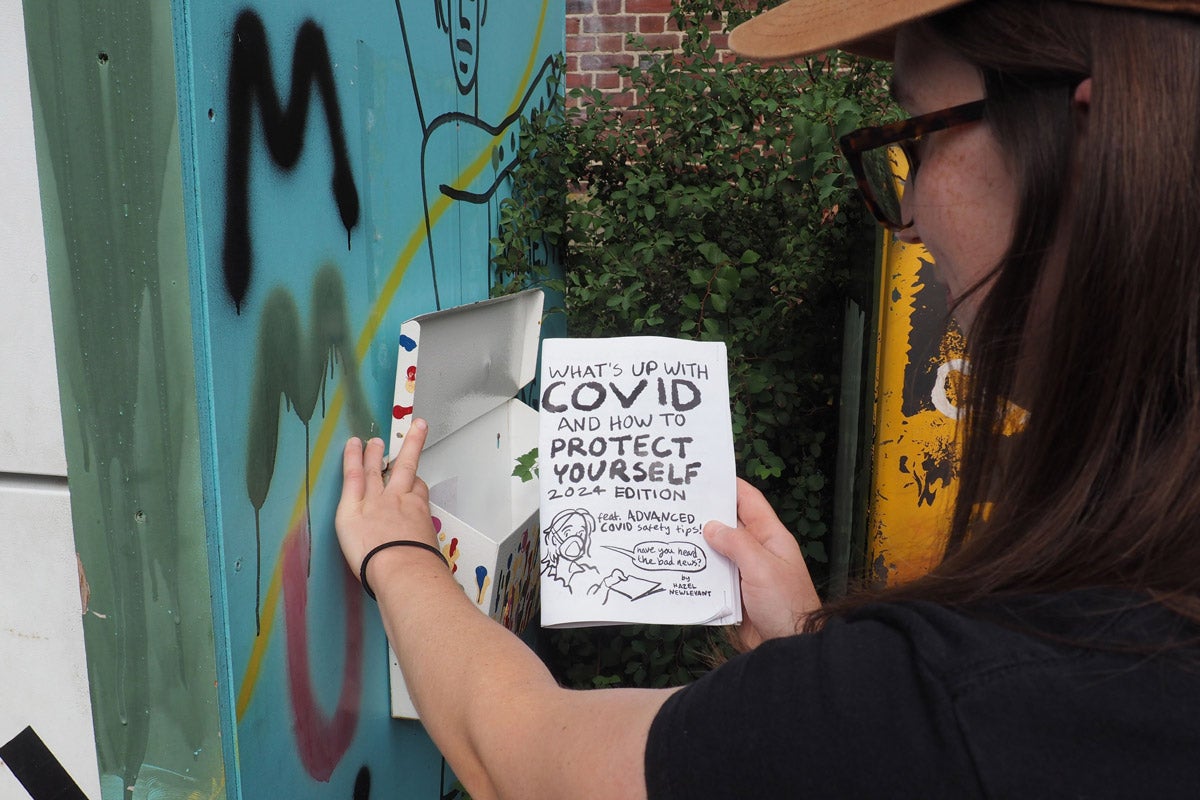

The Allston-Brighton community fridge has a box on the side to share “zines,” a small-circulation, self-published way to share art and information.

Credit: Alex LaSalvia / The Emancipator

The fridges are also a tool for racial equity. Black communities are more likely to be food-insecure and impacted by urban heat islands. When heat waves arrive in Boston, volunteers stock fridges with extra water and hydrating foods.

“We try to load water in the freezer as well, because that means it will double as an ice pack for somebody—a bottle of water that they can just apply directly on the neck, underarms, places to cool down quickly,” Ramette said.

Communities of color have a long history of hunger-fighting mutual aid programs. The Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast for Children Program, active from 1969 to 1980, fed 20,000 children in its first year alone. Many credit it for the expansion of the federal free breakfast program, one of the U.S. government’s largest welfare campaigns.

“I think the fridges, drawing on these legacies of Black and brown organizing, are carrying on this tradition of mutual aid,” Ramette said.

The popularity of community fridges took off during 2020 after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic emptied grocery shelves and boosted food insecurity rates.

How do the fridges actually work? Put simply, says Von Haynes, the fridges are “amplifications of the care that’s already going on in these spaces.”

Organizers vet potential host sites and their neighbors to make sure they have a strong relationship with the community. A site could be a restaurant, a church, or anywhere willing to provide permanent space and electricity. Fridges thrive wherever communities benefit from the sharing of resources—and are receptive to the idea.

“We don’t just drop fridges; they’re not vending machines,” Von Haynes said. “We want to just be a link in the chain and help support the folks doing the work. Without the community, none of these sites would be sustainable.”

The fridges are sourced from wherever organizers can find them.

“I helped get new refrigerators for the fridge project,” Ramette said. “So that would be calling a friend who had a pickup truck and being like, ‘Hey, do you have a free afternoon?’ Because this neighbor has donated their fridge from their second-floor apartment and we need to get it to this new location.”

There are local, national, and international groups that advocate for, and help install, community fridges—Von Haynes’ organization is one; Freedge is another—but their goal is to promote community adoption of the fridges, not run them.

“Long term, we try to get out of the way,” Von Haynes said. “We don’t have a business model that requires people to be in need.”

The Love Fridge is not a business or a charity, but a mutual aid group, Von Haynes added. The organization is run by members of the communities they operate in and makes decisions through consensus, not hierarchy or bureaucracy.

“We’re as flat as we can get and always working to be flatter,” he said.

No two community fridge groups operate the same way, but many cooperate to share lessons learned and wisdom gained. Ramette, for example, is in a Signal group chat for Massachusetts community fridge organizers, where they put out calls for food pick-ups, improve delivery logistics, and get advice on things like fridge weatherproofing.

“We’re not really taught to trust in our neighbors, and we’re not taught to be vulnerable and ask for help. The fridge really challenges those things.”

Megan Ramette, Allston-Brighton Community Fridge

A community fridge, as the name suggests, can’t function without support from the community—but Ramette says that despite pushback and obstacles, there are always neighbors to answer the call. Organizers seek supplies to help residents through hardships such as inclement weather, food shortages or COVID spikes, and community members are quick to rise to the occasion.

“We’re not really taught to trust in our neighbors, and we’re not taught to be vulnerable and ask for help,” Ramette said. “The fridge really challenges those things.”

Not every fridge makes it. John Chou, now a medical student in Boston, helped start a community fridge in 2020 in his hometown of Las Vegas, one that the city shut down over a zoning technicality.

Chou had previously volunteered with his local food bank. He was frustrated by the amount of food that spoiled before it could be distributed. Community fridges were picking up steam in 2020 and seemed like a logical solution. Chou searched across the city for somewhere to host one, ultimately finding a home in a “desolate” lot behind United Movement Organized Kindness, near an unhoused community experiencing some of the most extreme levels of food insecurity in the city.

“I think we were very naive in how we approached it,” Chou said. “I wanted it to be a tangible thing before we worried about everything else.”

There was an outpouring of community support online, but also backlash driven by anti-homelessness sentiments. Chou remembers seeing dozens of comments on Facebook spreading fear that people would poison the food or bomb the fridge or that the downtown district would be “overrun by homeless.”

Ramette has also seen community members turn against their fridge, calling it an eyesore, or saying they don’t like “the people it attracts.” “Just these incredibly racist and classist beliefs,” Ramette said.

In defending the fridges, she hopes to encourage people to reflect on why they have a negative reaction to mutual aid projects.

“When you’re in community with your neighbor, whether your neighbor is housed or unhoused, that just makes a stronger community, a more abundant community,” Ramette said.

The Allston-Brighton community fridge has had its own struggles. In May 2021, the property manager of the Allston host site cut power to the fridge without notice, spoiling hundreds of dollars’ worth of food. In August 2022, the fridge, now in Brighton, was found unplugged and moved out of view, and by night it was gone. They later learned the landlord had removed the fridge.

“We were very fortunate to be able to relocate and reconsolidate our efforts to keep the Brighton Center fridge going,” Ramette said. “For most fridges in the Greater Boston area, an eviction has led to the closure of their fridge project altogether.”

Chou said that in Las Vegas, organizers weren’t able to show enough proof that the fridge was decreasing food waste and hunger to maintain community support in the face of negative sentiments and city scrutiny.

“I think that is the biggest barrier with a lot of these projects,” Chou added. “You have to really believe in it, and it’s really hard to believe in it unless you have those measurable outcomes.”

Though academic research on the effectiveness of the community fridge is limited, several case studies affirm its transformative potential. One study concluded that the community’s attachment to and sense of ownership of a fridge was a key to its success.

The benefit of community fridges is abundantly clear to the people who sustain them.

“We’ve seen that it works,” Ramette said. “I think that the fact that people keep coming back to the fridge is a testament to the amount of support behind it.”

If your community doesn’t have a fridge and you want to open one, there are plenty of resources to help you get started.

“Mutual aid is human nature,” Von Haynes said. “It’s ripples in a pond. You may never see the actual end result, but just thinking about being hyperlocal first can open up a lot of doors.”

Lead image: A community member reaches into the Allston-Brighton community fridge in Boston. Credit: Alex LaSalvia / The Emancipator