Ideas

Three ways AI is improving public health

Today’s AI is well-suited to handle routine functions—even those that still require some expert judgment. AI can be trained with the same rules experts use; it doesn’t get bored or tired; and it works on smart phones, making it budget-friendly. Here are a few ways AI-based applications are improving health.

AI for monitoring postpartum mothers

The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world, and more than of half those deaths occur postpartum, often from cardiovascular or mental health problems. Penn Medicine in Philadelphia is using an AI chatbot, “Penny,” to keep in touch with mothers during those crucial first few postpartum weeks: answering their many questions, screening for postpartum depression, and asking about troubling symptoms to head off potentially fatal crises.

“We see patients every week leading up to the end of pregnancy, and then we send them home with a baby and say, ‘See you in six weeks!’ We should have continued contact,” says Kirstin Leitner, an obstetrician-gynecologist and Penn’s point person on the chatbot’s development.

Insurance, however, doesn’t cover postpartum weekly visits. The Penny bot helps fill that care gap. Patients can still call their doctor with questions and go to the ER if they feel they are having an emergency.

The chatbot answers texts 24/7 from postpartum mothers. Using natural language processing, Penny answers routine questions like, “Is my baby’s spitting up normal?” It also offers advice tailored to the patient’s situation—so mothers using formula get different information from those who are breastfeeding. And Penny asks the mother how she is and alerts a human clinician to anything serious. For example, Penny asks detailed questions about headaches to tease out whether they may indicate a life-threatening jump in blood pressure. Clinicians respond within a few hours, says Leitner. Some alerts are routed to a pediatrician or a lactation consultant as appropriate.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

About 1,800 patients have used Penny since the app was introduced in March 2020, and between five and 10 percent of those patients have generated at least one alert for a clinician’s attention, says Leitner, who is Penny’s “on call” OB/GYN. Penn collaborated with Memora Health, a developer of care navigation software.

Leitner says patients are often more comfortable asking the chatbot, rather than a doctor, about their own or their infants’ symptoms, and they appreciate that they don’t need to sit on hold waiting for a doctor or nurse. Penny also can administer standardized screening questionnaires for postpartum depression. Of the 40 percent of patients who completed the screening, one in four scored high enough to signal a risk of depression, and Penny alerted a clinician to follow up with them individually.

Penn is still working out how it might charge patients or their insurers for Penny’s services, Leitner says. Meanwhile, Penn is monitoring such metrics as patient satisfaction, breastfeeding rates, and patients’ attendance at scheduled follow-up visits.

AI vs. superbugs

One challenge in the fight against antibiotic-resistant infections in low and middle-income countries has been interpreting antibiograms, the bacterial cultures used to show which antibiotics are effective for a particular bug. Antibiograms require trained microbiologists to interpret them and recommend the best course of treatment, and such specialists are few in these countries. Clinicians treating an infection can wait days for a culture to be read by a far-away specialist; meanwhile, patients get sicker. Another option is to rely on the best guess of a local lab technician, but that can result in giving patients ineffective drugs that can also make the microbe even more resistant.

Enter Antibiogo, a free Android-based AI-enabled phone app that, as its name suggests, reads antibiograms on the go. Developed by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Foundation, it analyzes an image of the culture taken with a phone camera and interprets it based on the same rules used by microbiologists. Antibiogram cultures are made on a plate containing discs of several antibiotics. The app measures the “zones of inhibition”—the patterns of dead bacteria around the discs that show how well each antibiotic fights the microbe—and identifies the best treatment.

Antibiogo takes a burden off lab techs who haven’t been trained to interpret these tests, says Nada Malou, an antimicrobial resistance specialist at the MSF Foundation who manages the Antibiogo program. The group published a paper in Nature showing the app performed as well as specialist human interpreters (“the gold standard”). In a later trial run with general lab techs in Mali, the app corrected 45 percent of their interpretations.

The European Union in 2022 approved Antibiogo as an in-vitro diagnostic device. It is currently being used in MSF labs in Yemen, Mali, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Jordan, and so far has analyzed cultures from about 500 patients. The organization plans to scale up its cooperation with national health authorities in several African countries, starting with Mali, which began using the app in seven of its national labs in September 2023.

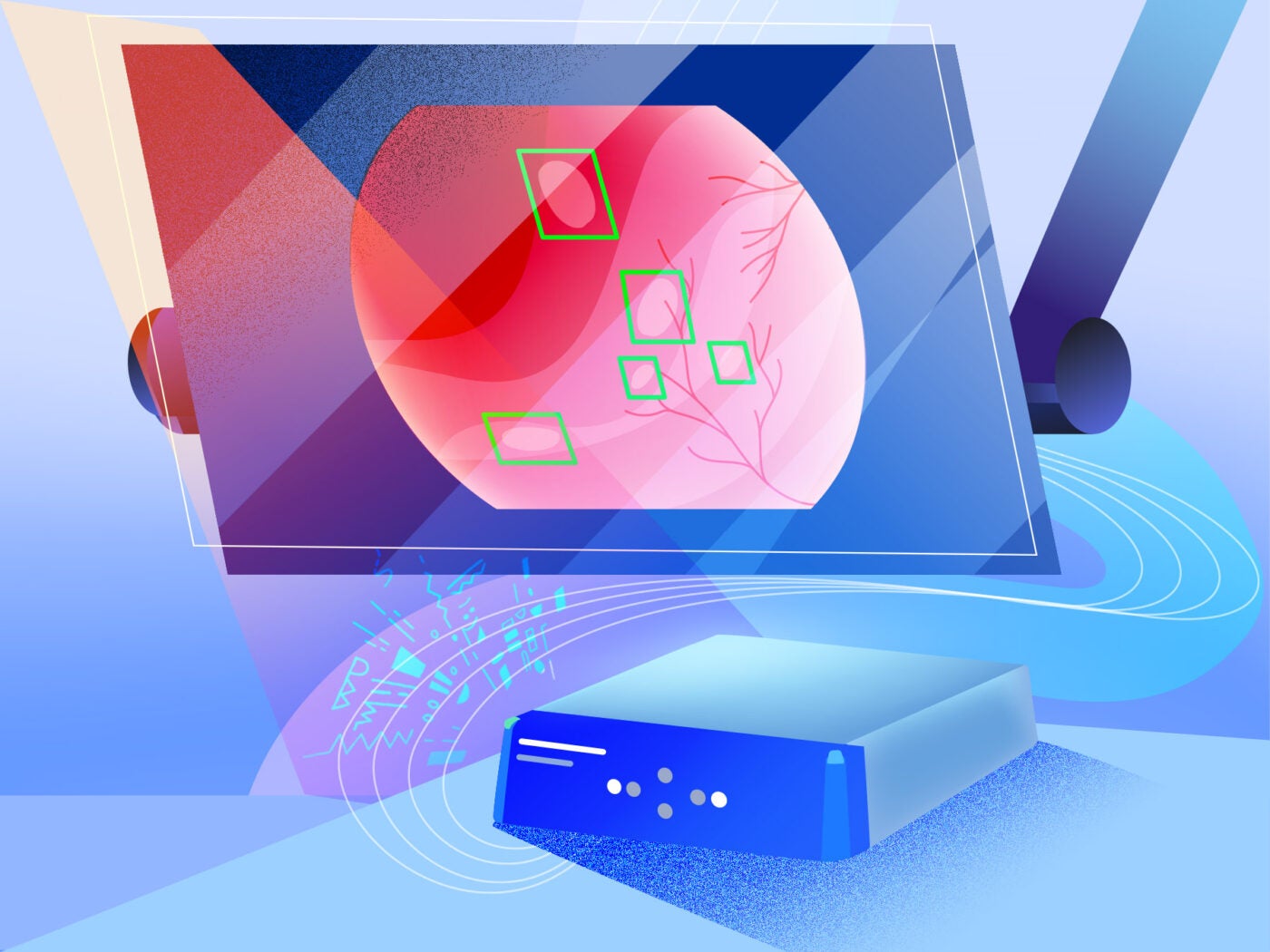

AI and cancer screening: finding growths that humans miss

Colorectal cancer is the second-most common cancer in the U.S. and the second leading cause of cancer deaths. One of the most effective tools for fighting these cancers is a routine screening colonoscopy, which Americans older than 45 are urged to get at least once a decade (more often if they have risk factors for colon cancer). Studies have shown that colonoscopies can reduce new cases of colorectal cancers by up to 69 percent and cut the risk of death from the disease by 88 percent. The trick is to spot adenomas, or precancerous polyps, that can be removed during the procedure.

That’s where AI comes in. AI is particularly adept at reviewing medical images: Of the almost 700 AI applications currently approved by the FDA, three out of four involve medical imaging.

Rush Health System in Chicago has outfitted all its endoscopy suites with GI Genius, a device that detects suspected adenomas during a colonoscopy and brings them to the attention of a gastroenterologist for further evaluation and possible removal. About 6,800 colonoscopies a year take place at Rush, about 40 percent of them routine screenings. Where GI Genius helps most is in three areas: finding very small adenomas, differentiating suspicious growths from harmless ones, and improving detection of multiple adenomas during an exam. The goal in using GI Genius is to increase consistency without increasing false positives, says Rush gastroenterologist Salina Lee.

Rush has been using GI Genius since spring 2022 and is gathering data on effectiveness. It’s too early to gauge the impact on cancers averted and lives saved, but Lee cites research showing that each one percent increase in an endoscopist’s adenoma detection rate was associated with a three percent decrease in the risk of patients developing a fatal colorectal cancer before their next screening. “The benefits are clear,” she says.