Ideas

Elevator Pitch: World Shoe Fund

Footwear is often a mere fashion accessory, but Manny Ohonme sees it as life-changing. The native of Nigeria received his first pair of shoes at age nine, went to a basketball camp that set him on the path toward a college scholarship in the United States, earned a master’s degree, and decided shoes could change the world. He founded the nonprofit Samaritan’s Feet in 2003, which has distributed more than nine million pairs of shoes to people who need them. Ohonme has launched other projects, including the World Shoe Fund in 2023. Based in Ghana, where it manufactures shoes, the group now operates in 12 countries and has sold 1.5 million pairs of shoes for humanitarian purposes.

Its biggest goal is fighting soil-borne diseases, which helps break the chronic cycle of poverty. A side benefit of avoiding disease is that it helps keep kids in school. Operating the shoe fund as a business makes it less reliant on donations. “Charity is not sustainable for lasting change,” says Courtney Cash, president of the World Shoe Fund. “We must invest in scalable market-based solutions to see true transformative social impact.”

Cash talked with Harvard Public Health’s Christina Williams about the World Shoe Fund’s goals. This interview was edited and condensed.

Harvard Public Health: What public health purpose does your idea serve?

Courtney Cash: We promote positive hygiene practice and shoe-wearing. There were a lot of different issues related to people going barefoot in contaminated soil—worms, soil-transmitted helminths, podoconiosis, jiggers [tunga penetrans], and other pathogens that would enter through the feet. So, we began to look at whether shoes would act as a natural prophylactic against disease.

Manny and Tracie Ohonme, co-founders of the World Shoe Fund, work alongside Sierra Leone First Lady Fatima Maada Bio, to distribute shoes and sanitary pads to more than 3,000 girls in Koidu.

Courtney Cash

HPH: Who is funding it and do you have access to capital?

Cash: One of our partners in our original pilot in Ghana was Sanford Health Systems [in Sioux Falls, South Dakota]. Denny Sanford provided catalytic funding for us to do our initial prototype and pilot. He [also] gave us the investment that allowed us to start a factory in Okasembo, Ghana.

Our regional factory in Ghana has the capacity to manufacture five million shoes per year. We have a phased expansion model that starts with a humanitarian partnership, [followed by] retail demand, a distribution center, and a micro-factory. With this plan in action, we expect to have two additional regional factories in Central and Southern Africa in the next few years.

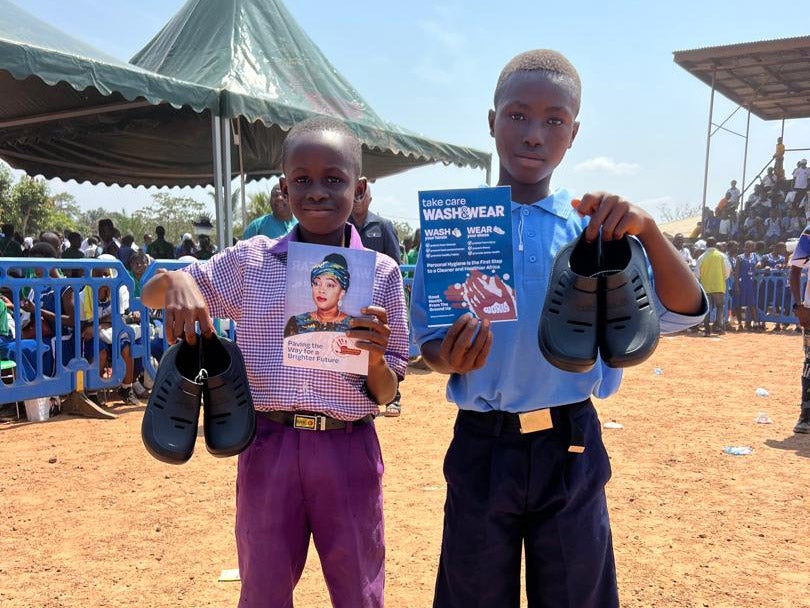

Two boys in the town of Koidu, Sierra Leone pose with the shoes and hygiene materials they received at a distribution hosted by Bio.

Courtney Cash

HPH: How do you get paid for it, and who are your clients or customers?

Cash: Global health agencies, like the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), [the Gates Foundation], and CIFF [Children’s Investment Fund Foundation], become the intermediary funder to our government partners. For example, the minister of local government in Rwanda wants to use our shoes for a health and hygiene initiative — promote hygiene, promote vaccines, [tuberculosis] testing, and prenatal, malaria, and HIV screenings for moms. Together, we would go to a third party that actually funds the procurement of the shoes.

In December of this past year, we launched a retail brand of our shoe with multiple colors and have a clog and a slide that are coming out for sale in Ghana and soon in the United States. That’s our long-term sustainability [plan]. To date, we’ve sold 1.5 million pairs of shoes for humanitarian purposes.

HPH: What are your obstacles to success?

Cash: We deal with traditional obstacles to setting up your business lines, like: How do we create a business-to-consumer product in Africa? How do we create a business-to-business product? How do we sell a humanitarian cause? How do we get a third party to pay for the shoes to give away to the end user? How do we not just stay as a donation-based humanitarian organization? [In Africa] on the humanitarian [side], we’re working through implementation partners that have been doing it for years, governments that know what they’re doing. But we’re trying to set up retail and economic development in Africa, a very fragmented country-to-country market. The way we started to address that one is through co-creation and working with people on the ground on design and distribution models, [not] Americans telling the Africans what they should do. We need to bring what we can to the table, but we need to listen and learn in the African context as to the best way that we’re going to sell shoes on that continent.

Because our partnerships have all been affected by the “USAID pause,” we are focusing more on the local government partnerships and our alignment with the WHO Roadmap 2023, the U.N. Sustainable Goals, and the UNICEF WASH model we’ve incorporated into the product in our WASH&WEAR distribution model.

HPH: How do you show your value or impact?

Cash: In Sierra Leone, we [recently] distributed shoes to 10,000 girls in three days. Each girl got one year’s worth of sanitary pads and the shoes that they needed. There’s also a lot of qualitative data that we’re seeing. To give you one example out of Rwanda, kids were getting to school and saying that [their feet] don’t hurt as much. What the teachers were saying is test scores were better, attendance was better … because [kids] had proper footwear. Our randomized control trial, done in collaboration with Move Up Global, showed a 34 percent decrease of worm-infected diseases in program participants. The group’s school attendance also increased by 15 percent. So, there’s never any question about whether it’s the shoes. These shoes bring real change, and when we look at value, it really is all about the shoe.