Opinion

Let’s end the war on obesity

In the United States, we “wage war” against all kinds of things: the war on poverty, the war on drugs, the war on crime. In my experience, one “war” in particular seems to be a catastrophic failure: the war on obesity.

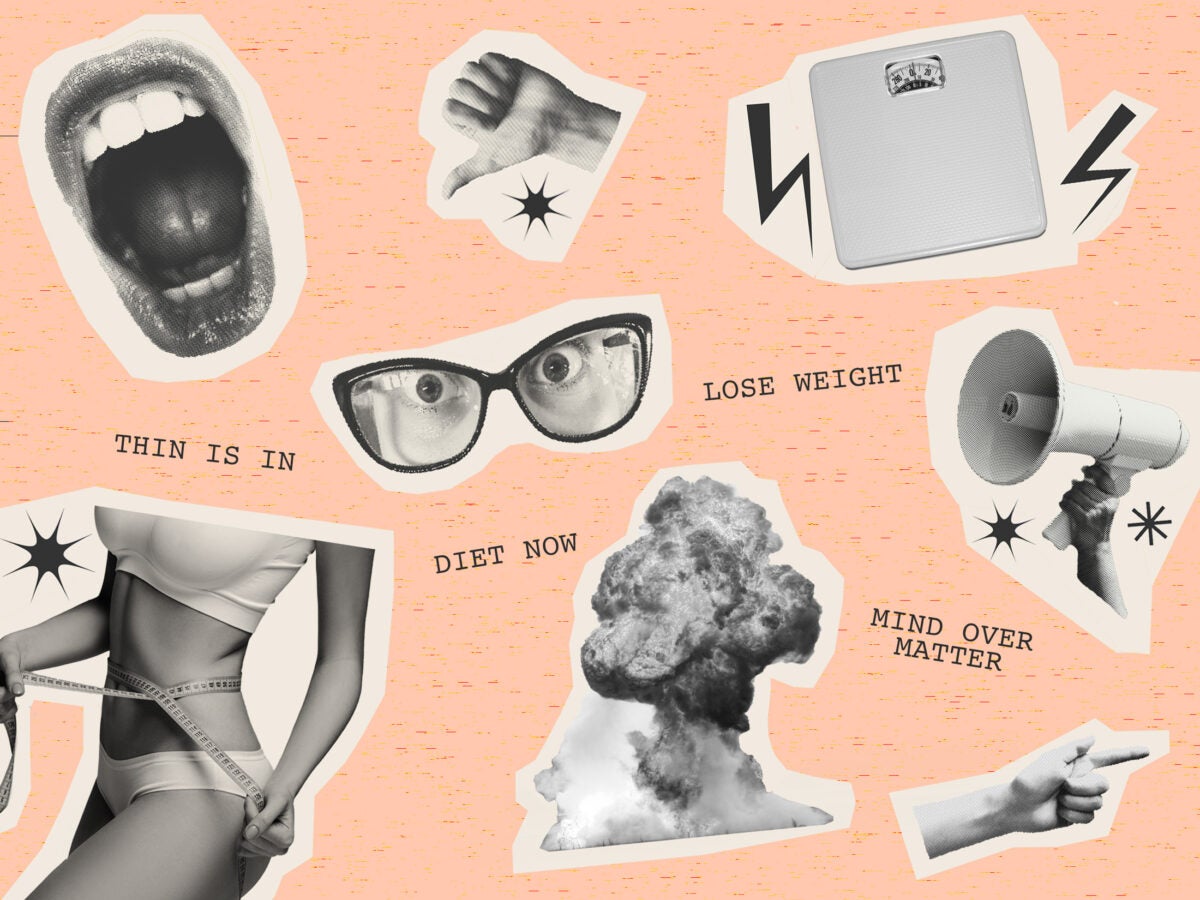

For decades, the medical and public health fields, buttressed by the media, have waged this growing war against obesity. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) declared obesity a disease in 1998, swiftly transforming people’s body size into a sickness. Headlines like “Obesity bigger threat than terrorism?” peppered newspapers when U.S. Surgeon General Richard Carmona called obesity the “terror within”—implying a threat akin to terrorism in the years following 9/11. Commercial diet plans like the Atkins Diet or Weight Watchers capitalized on people’s fear of weight gain. And toxic reality television shows like “Are You Hot?” and “The Biggest Loser” reinforced the message that a healthy, ideal body was a skinny one.

It seemed as though we were progressing beyond dangerous diet culture, but this year, I have seen troubling signs of backsliding. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recently released a new, controversial guideline recommending bariatric surgery for teens as young as 13, and weight loss medication for children as young as eight. Thanks to celebrity endorsement, thousands of Americans began taking the prescription drug Ozempic for weight loss, causing a national shortage that left those with type 2 diabetes without a necessary medication used to control their blood sugar levels. Celebrities are taking to social media to share “wellness routines” that disguise starvation as fasting and bone broth as breakfast.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

While I’m elated to see younger generations separating health from weight, so much of what has happened this year shows me that weight bias persists, and that celebrities, citizens, and medical professionals still aren’t willing to accept that a fat body can also be a healthy (and dare I say, beautiful) body.

I know from personal experience just how dangerous this can be.

As a teenager growing up in the early 2000s, I was bombarded by this war on obesity—not only from the media and society at large, but from doctors, teachers, and even family members. The message I received boiled down to one thing: your body needs to shrink. The fear? If I wasn’t thin, I wasn’t healthy. But my attempts to get thin led to what I would argue are far worse mental and physical health outcomes than a few extra pounds: years of battling eating disorders accompanied by debilitating depression, anxiety, and shame.

To be clear, I didn’t grow up medically obese or overweight. As a matter of fact, I was healthy by all measures. My blood pressure, heart rate, and other health standards were always normal. And yet, my mother and doctor still encouraged me to lose weight. It was only years later, after much pain, that I would recognize losing weight is not a definitive path to better health.

I’m now proudly in recovery. The crux of my journey came when I took a closer look at the role of weight bias in my life and the culture that surrounded me growing up. At first, I unfairly blamed my mother, wondering why she would ever encourage me to eliminate carbohydrates or try to lose weight at such a young age. Later, I came to understand that as a devoted mother, she was simply delivering recommendations from medical and public health experts at the time.

As a teenager growing up in the early 2000s, I was bombarded by this war on obesity. The message I received boiled down to one thing: your body needs to shrink.

I fear the pendulum has swung back to the point where new generations will receive the same damaging messages.

Growing evidence shows that experiencing weight discrimination leads to negative health outcomes and behaviors that, ironically, “promote and exacerbate obesity.” Plus, weight-loss surgery isn’t a very effective treatment for adolescents: longer follow-up studies show weight regain in 50 percent of patients, plus reduced bone mass and nutritional deficiencies in 90 percent of patients.

Still, the AAP guideline promoting weight loss surgery is just one example of a bigger problem. As long as health care professionals and influencers continue to preach the gospel of skinny, the burden of this “epidemic” will remain an individual one—when, in reality, the solutions for improved health are wider and systemic.

Here’s what we should do instead:

- First, let’s eliminate weight stigma, especially in health care settings. Public health and medical professionals need to stop trying to “treat obesity” (i.e. encourage weight loss), according to a study by the Harvard Chan School’s Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders. Instead, we need to focus on overall health and end weight discrimination, which can lead to negative consequences including higher cardiovascular risks, avoidance of health care, and reduction in health-promoting behaviors. If weight loss worked as a treatment, this “war” would have ended years ago, but research shows rising rates of obesity in both children and adults.

- Second, let’s take dieting out of health recommendations altogether. An older, but still significant, meta study by researchers at UCLA found that a majority of dieters regain the weight they lost, plus more, and that diets do not lead to sustained weight loss or health benefits for the majority of people. Dieting can also lead to the development of eating disorders which, according to the NIH, can be much more detrimental to health than obesity.

- Third, let’s find public health solutions that address the systemic issues contributing to poor health outcomes and wellbeing. Policy-level recommendations include incentivizing supermarket development in food deserts, adjusting agriculture policy to increase the planting and selling of fresh fruits and veggies, or building communities with active transportation and physical activity in mind.

Before we put young teens under the knife or prescribe Ozempic for weight loss, let’s find solutions like these so that larger-bodied individuals can stop fighting against shame, stigma, and the associated negative health consequences, and start experiencing the dignity that comes with improved confidence around food, movement, our bodies, and ourselves.

I’m waving the white flag: let’s finally put down our weapons and end this imagined war on obesity.

Source images: Softulka / iStock, master1305 / iStock, RASimon / iStock, William_Potter / iStock.