Opinion

Let’s reinvent the rape kit

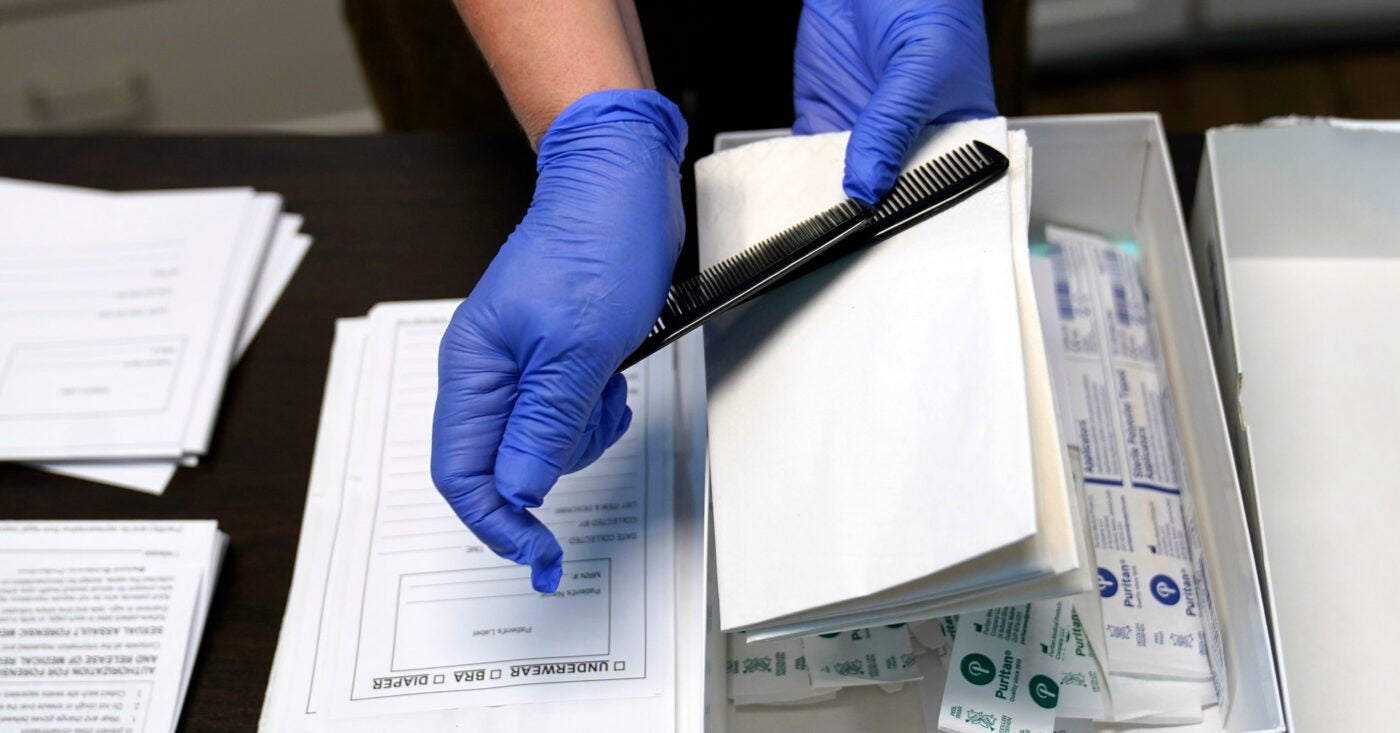

In a hospital somewhere right now, a nurse is examining a sexual assault survivor’s body in order to collect evidence. The nurse stuffs Q-tip-like swabs into envelopes, fills out many paper forms, and packs all of that into a cardboard box. Then the box, called a rape kit, will go to a shelf in a dank basement. It could be years before someone opens that box and tests the DNA inside it. And maybe the box will never be opened at all.

The rape kit is caught in a time warp. Even while other forensic tools have leapt into the digital age, it remains stuck in the 1970s.

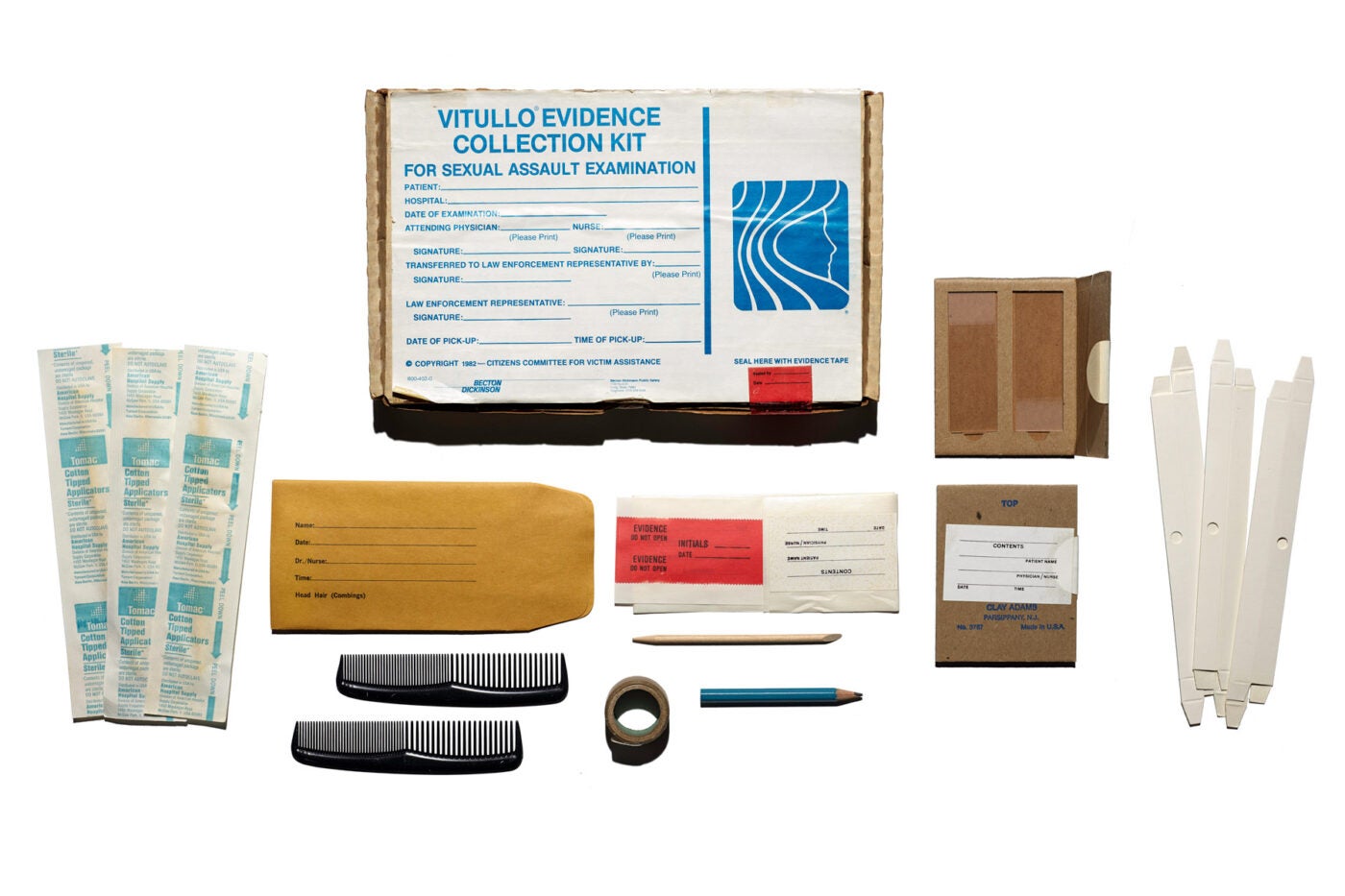

This is no knock on Martha Goddard, the activist who created and popularized the rape kit fifty years ago. Back then, women were routinely accused of “crying rape” and denied the chance to submit evidence. So Goddard trained nurses to perform a physical examination of women’ bodies, collecting evidence so meticulously that the victim’s story would stand up in court. At that time, DNA identification didn’t exist. Police officers called each other on car radios. Nurses recorded their notes on paper.

Even though social attitudes and technology have changed radically in the last 50 years, the rape kit remains stuck in the same era as the rotary phone.

One of the original rape kits introduced almost 50 years ago.

Division of Medicine and Science, National Museum of American History and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

I’ve spent the last five years digging deep into the history of American crime forensics, writing a widely read 2020 New York Times story about the origins of the rape kit and interviewing people for a forthcoming book. I’ve learned that the rape kit is the unsung hero of forensics—when used correctly, it can identify violent criminals and also prevent wrongly accused men from going to prison. But unfortunately, it has never really been given a chance to work. It could be so much better.

We need to talk about the rape kit because it’s oddly invisible. Most people seem to know—vaguely—that the kit exists. But few people are aware of how it works or why it is endangered. Here are four problem areas:

Problem 1: Accessibility and Inclusivity

While more than 100,000 Americans each year decide to submit evidence after a sexual assault, that represents only 1 in 5 survivors. Myriad obstacles exist: Fewer than 20 percent of American hospitals keep a forensic nurse on staff, meaning that many survivors must be able to drive to hospitals that are hours away for an exam. The exam itself takes about five hours, after what is usually an hours-long wait in an emergency room.

The exam is invasive and can retraumatize a survivor. Then there’s the risk of intimidation by police officers, who might discourage survivors from submitting evidence and may even harass and threaten them.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

We need an entirely different system, one in which the rape kit and sexual assault care are within walking distance. We also need a forensic evidence system attuned to the dilemmas faced by non-White survivors. Native American women are more than twice as likely to be raped than non-native women in the United States, and yet they face much higher barriers when they try to hold the perpetrators accountable. What would it take to build a culturally appropriate system designed for people who live on reservations?

Black women, many of whom live in communities that have been shattered by police brutality, are less inclined than other groups to seek help from forensic nurses or the criminal justice system. “Sexual assaults against Black women are underreported, under-investigated, and under-prosecuted,” law professor Michelle S. Jacobs has written. What would it take to create a rape-kit system that works for women of color?

Every time a survivor reports her attack, she helps to strengthen the rape-kit system as a whole—the sample collected from her body could match DNA in several other kits. This is why it’s crucial to reach out to all survivors and learn what would help them to contribute evidence.

Problem 2: The Rape Kit Backlog

In 2010, a pile of untested rape kits discovered in a Detroit parking garage created a scandal that led cities and states to ultimately find more than 400,000 untested kits nationwide. Even when crime labs do test the DNA samples in rape kits, it’s often difficult for survivors and their lawyers to find out the results of those tests and track the progress of cases.

Many states are enacting half-solutions to the backlog problem, such as adding software that can track the kits as if they were UPS packages. These efforts have been tangled up in red tape—and it’s not clear how all of the local tracking systems will work together. Wouldn’t it make more sense to reimagine the kit itself as a digital device? Increasingly, the evidence in sexual assault cases is digital—and may include text messages, videos, and screenshots. What if nurses could test DNA samples in real time and store the results in virtual “kits,” along with photos, audio, and other digital records?

Problem 3: Standardization

Martha Goddard intended to create a national forensics system that would be standardized across all cities and states. Nearly 50 years later, that still hasn’t happened. There is no single rape kit. Every state has its own set of protocols and rules, which leads to overstuffed rape kits that are difficult for medical staff to use (to see how complicated it can be, look at this video by the designer Antya Waegemann, who demonstrates the process of unpacking New York state’s kit). How can we engage politically, technically, and practically to build a standardized national system, so that every hospital performs the forensic exam in the same way?

Every time a survivor reports her attack, she helps to strengthen the rape-kit system as a whole.

Problem 4: Preventing False Convictions

Since 2010, using DNA evidence from rape kits has meant fewer Black men have been wrongfully convicted for sexual assaults than in the decades before. Still, we could do far better. Thousands of innocent people are languishing in our prisons, unable to see a path to justice. How can we create a system that makes it easier for lawyers and their clients to access rape-kit data that can overturn wrongful convictions?

Above all, we need survivors, lawyers, crime lab workers, engineers, nurses, and others coming together to dream up new designs for the rape kit. A hackathon is one great way to bring new thinking to bear on the sexual-assault forensics system. Hackathons invite diverse groups of people to brainstorm solutions to a problem. For instance, in 2014 the MIT Media Lab hosted a hackathon to reinvent the breast pump, gathering mothers, designers, engineers and pediatricians; it helped lead to battery-powered pumps and pumps that could fit inside a bra.

That kind of energy and inspiration could be crucial to the change we need here—not just for the tool of the rape kit itself, but the policy and legal systems that are supposed to bring justice to survivors of sexual assault.

For more information or to contribute to making a hackathon happen, reach out via this form.

Top image: A sexual assault evidence collection kit, commonly called a rape kit, is unpacked in an examination room on Wednesday, Aug. 31, 2022, in Austin, Texas. (Eric Gay / AP Photo)