Essay

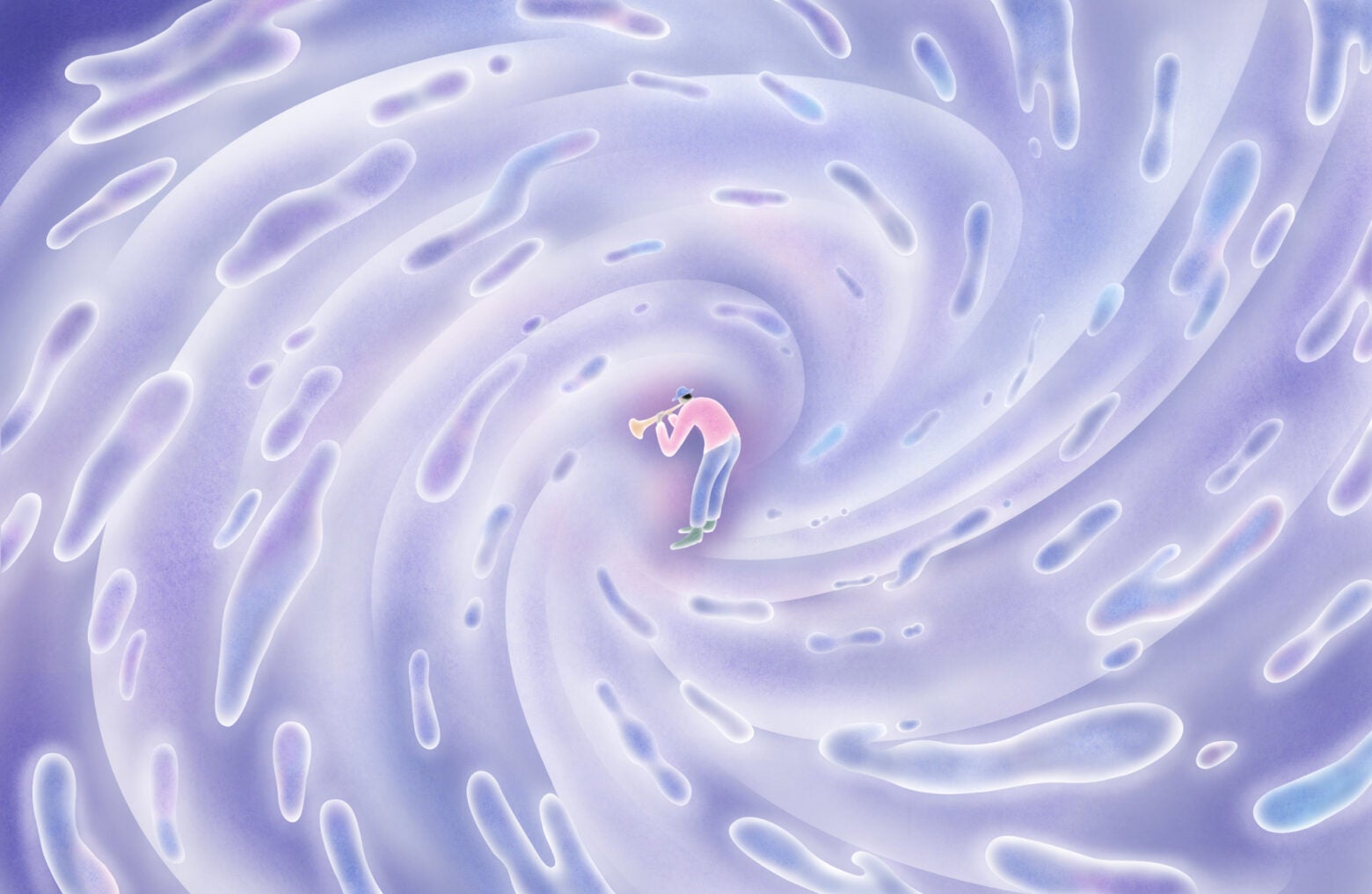

In New Orleans, using music to counter hurricanes

There’s a song for nearly everything that happens in New Orleans, even a hurricane. Songs are cathartic. Once a major storm passes, local musicians start working on new material. Or they’ll adapt an old song to fit the watery particulars of a more current emergency. The troubadour John Boutté did that in 2006 at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. He updated the lyrics to “Louisiana 1927“—the Randy Newman masterwork detailing a historic river flood—to reflect the shortcomings of the federal response to Hurricane Katrina. Boutté’s performance became one of the most memorable in festival history. Then, the Free Agents Brass Band released “We Made It Through That Water,” a hip hop variation on the Negro spiritual “Wade in the Water.” The Free Agents also were provoked by governmental response to the storm and added a rap from the perspective of a returning evacuee:

Whatever they do, I can’t turn my back

I was born right here, so right here

is where I’m at

Send them troops home

Look daddy this ain’t Iraq

Tell FEMA we gon’ need more than ten stacks

And yet, few have been inspired to write memorably about Hurricane Ida, which made landfall in 2021, exactly 16 years to the day when Katrina roared ashore. Ida is the second strongest storm on record to reach Louisiana, but its lyrical potential likely won’t be explored until more time has passed. Many here are holding out still for their insurance companies, or carpenters, or roofers, or electricians to come through. Catharsis will have to wait.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Meteorologists say Ida “grazed” New Orleans. But people in the French Quarter heard the silence of the eye passing in frightening proximity. The storm also pushed a major electrical tower into the Mississippi River, before bashing its way east. Statewide, at least 26 people died, including 10 from excessive heat in Orleans Parish during the subsequent power outage. Months later, the effects of Ida remain evident across the city. Just look up. There are crape myrtles missing from Canal Boulevard, live oaks dead on Broad Street, magnolias leaning on Jefferson Avenue, Italian cypresses shocked off Downman Road. Street signs are gone or listing. Blue tarps on rooftops flap in the wind.

Recovery has been slow for the obvious reasons—the coronavirus, worker and supply shortages, and the limited means of people in flood zones. And while music helps communities cope with trauma, it would take quite a rhyming dictionary to come up with one song that covers Ida’s mess. Public school workers in St. Charles Parish came close in 2021 when they parodied the Mariah Carey song “All I Want for Christmas Is You.” Putting romance aside, they sang “All I Want for Christmas Is a Roof.” Hopefully, they won’t need the same lyrics this Christmas. Hurricane season begins in June.

Music has its limits. Songs can record a cataclysm but won’t mention every detail. Nor can they reshingle a roofline, appeal a FEMA decision, replenish a savings account, or substitute for dialogue with an experienced mental health professional. And yet, in the short term, music leavens. It comforts and condoles. It gives structure to overwhelming emotion and helps time pass more fluidly when nothing seems to be happening and no one is on the way.

People emptying their refrigerators after a power outage are looking for solace they won’t find in the crisper. At times, solace is in the songs that make for belly laughs, providing emotional release from the horror show in the casserole dish. Without letting go of at least some of the anxieties brought on by a single hurricane or hurricane season, it would be far more difficult for them to face the next one. And the one after that. And the one after that. “You have to have humor growing up here in New Orleans,” the bounce music queen Big Freedia once told me. Freedia, like thousands of other people across the city, was stranded for days on a bridge after Katrina, then evacuated out of state. “You have to have something to keep you laughing.”

Sometimes the laugh is more important than the songs. When I was senior editor of NPR’s Weekend Edition, we interviewed Madan Kataria, a physician who’d started daily laughter clubs across India. At first, people shared jokes. Then, they ditched the jokes and laughed anyway, mastering 20 to 30 different styles, including hearty, pigeon, swinging, giggle, and the like. The sessions, he said, better prepared them to face their troubles. “Imagine … people doing all that together,” Kataria had said. “You feel so good, so nice. It’s like a meditation.” Now, his website reports laughter yoga is in 110 nations, apparently releasing endorphins, mitigating pain, and strengthening immune systems worldwide.

In New Orleans, the closest laughter yoga teacher lives just beyond city limits. But my friend Bette Cole, a retired law professor, told me about an informal crying group she helped start years ago, just before the pandemic shutdown. They share songs. The selections aren’t necessarily sad, she said, but rather “something so moving, you want someone else to know about it.” Like the pianist Lang Lang, for example, playing “Intermezzo No. 1 in E Minor” by Ponce. Or the pianist Víkingur Ólafsson handling the Glass “Étude No. 5.” Or “Va, Pensiero” (Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves) from the Verdi opera Nabucco. Tears, like laughter, offer a kind of emotive cleansing as essential to humans as breathing.

Bette also chose Rosemary Clooney singing the Fain and Kahal classic “I’ll Be Seeing You.” That’s a song her group, and indeed all New Orleanians, can relate to, especially when we say goodbye to each other in those fretful hours before a hurricane passes through.

I’ll find you

In the morning sun

And when the night is new

I’ll be looking at the moon

But I’ll be seeing you

Ida may not be balladworthy to Louisiana musicians. But heaven help us when another storm is. Mercifully, the levees around New Orleans held last year, even when they broke 20 miles away in the town of Jean Lafitte. And yet, it’s the yin and yang of it, the vagaries of triumph and catastrophe that pummel the nerves. Mapmakers may be slow making the change, but people here know that the tip of Louisiana’s boot is already gone. So is much of the sole.

Carlos Miguel Prieto, the Mexican-born and enormously popular conductor of the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra, took that job just weeks before Katrina wrecked New Orleans. In October 2005, at the invitation of the Nashville Symphony, he conducted his orchestra’s first performance after the disaster—the Largo movement from Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5, a selection about facing calamity that brought its original 1937 audience to tears. The Philharmonic, with guest violinist Mark O’Connor, also played a soul-stirring “Amazing Grace,” reminding listeners that the most healing power of music, its central message, as Prieto once told me, is that, “I am lucky, first of all, to be alive.”

Hurricane season ends in November. The song I keep ready in the interim, along with the hip waders and flashlights, was sung by one of the best among us in Louisiana. Johnny Adams, a.k.a the “Tan Canary,” could sing just about anything, in any key. Whether the New Orleans skyline is falling away from my car’s rearview mirror as I leave the city or filling the windshield as I return, I want to hear Johnny sing “There Is Always One More Time,” written by the great Doc Pomus. It’s tailored to fit.

And if your dreams go bad

Every one that you had

That don’t mean some dreams

Can’t come true

‘Cause it’s funny about dreams

Just as strange as it seems

There is always one more time

Now, THAT’S a crying song. I’m gonna call Bette.