Moses Muthomi, an herbalist in Nairobi, has developed two herbal remedies that address the effects of diabetes on the endocrine system and glucagon levels. His daughter Fridah has Type 2 diabetes. “I have so far successfully treated around one hundred people who had diabetes,” says Muthomi, including Fridah. She was able to stop using insulin two years ago. Lenny Rashid Ruvaga

Feature

Can traditional medicine help solve Kenya’s diabetes crisis?

During Paul Kiplangat’s career as a Kenyan public health officer, the policies governing the country’s health centers would not have allowed them to offer traditional remedies for diseases. But when he was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes seven years ago, he experienced complications with his prescribed medication.

“I used to have frequent headaches and a burning sensation in my toes,” says Kiplangat, now 61, of the side effects from Glucophage and other drugs he was prescribed. A colleague said his diabetic father saw tremendous improvement after switching to herbal medicine, so Kiplangat opted to give it a shot. He gradually reduced his intake of conventional medicine and started an herbal regimen, along with lifestyle changes that included healthy eating habits. After three months, his blood sugar level had fallen to a healthy range. “Once I started using herbal medicine, the pain and headaches disappeared, and now I am completely healed and okay,” he says.

Herbal remedies have been included in research into traditional medicines by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) for more than four decades. But 15 years ago, researchers became more intent on looking for novel compounds to help manage and treat non-communicable diseases, including diabetes. “Access to diabetes care in low- and middle-income countries is a major challenge,” says Elsa Morandat, head of policy and programme at the World Diabetes Foundation. Morandat says both the cost of treatment and the lack of proper equipment across health systems create care gaps.

The condition has been on the rise in Kenya, from 872,000 cases 10 years ago to 2.1 million people, or four percent of adults, in 2022. Between now and 2045, Africa is projected to have the highest global increase in people living with diabetes.

“Diabetes is a huge public health problem in Kenya,” says Esther Matu-Macharia, the deputy director at KEMRI’s Centre for Community Driven Research (CCDR), which focuses on improving health outcomes. (The research itself is carried out by another KEMRI unit, the Centre for Traditional Medicine and Drug Research.) Treating it is costly—even with government subsidies, on average a vial of rapid-acting insulin costs around 4,300 shillings, or U.S. $33, and a patient may need three to four vials monthly, an almost 30 billion shillings, or $230 million, annual burden on the economy. With almost 9 million Kenyans—7.8 percent of its population—living in extreme poverty, on less than the equivalent of $2.15 per day, officials estimate that 40 percent of Kenyans with diabetes, some 750,000 people, do not receive treatment.

Several years ago, Matu-Macharia investigated whether aloe, which is plentiful in Kenya, might provide a cheaper alternative to insulin. She knew traditional healers have long used aloe extracts to treat symptoms of diabetes, such as reducing blood glucose levels, and that there had been some research. She and some colleagues took extracts from the leaves of two aloe plants indigenous to Kenya (Aloe lateritia and Aloe secundiflora) and tested them on diabetic mice through injection. Her study, published in the European Journal of Medicinal Plants, found the extracts reduced blood sugar levels in the mice while also protecting pancreatic beta cells from damage. In addition, it found the phytochemicals (part of a plant’s immune system) in the extracts acted as antioxidants, which help the immune system fight chronic diseases like diabetes.

KEMRI has subsequently partnered with hundreds of traditional healers and herbalists from around the country to tap into their knowledge on the treatment of diabetes, developed and refined over generations. Herbalists focus on plant-based remedies, while healers also incorporate holistic approaches to wellbeing.

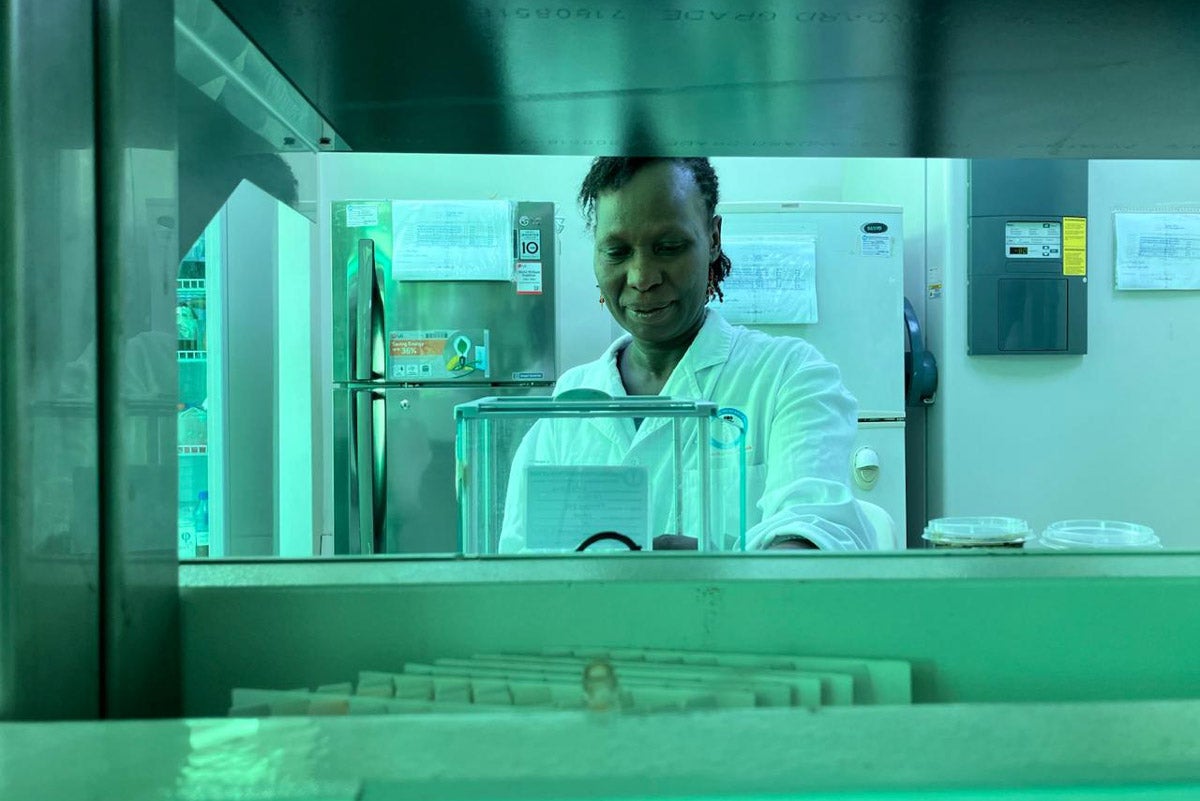

Esther Matu-Macharia works in her lab.

Lenny Rashid Ruvaga

A worldwide phenomenon

KEMRI’s work fits into the World Health Organization’s multi-year effort to create standards and expand the evidence base for traditional medicine. It is an acknowledgment of the widespread use of traditional methods, especially in rural and remote areas, and also an effort to address concerns about traditional approaches. For diabetes, although some studies have suggested using both traditional and conventional medicines to manage and treat the disease, the data is most clear that traditional knowledge has a place “in the early management of diabetes,” says Ahmed Ogwell Ouma, a senior advisor at the U.N. Foundation. He says for more advanced cases traditional approaches may not be effective.

That is similar to the official line of Kenya’s Ministry of Health. “Some [traditional remedies] are effective in the treatment of diabetes but it should be noted that these remedies do not cure diabetes,” says Pauline Duya, head of the Ministry’s Division of Traditional and Alternative Medicine. She says patients ought to be cautious in using traditional herbs.

The much lower cost of traditional treatments is one reason why KEMRI is pursuing its research, says Matu-Macharia. Plus, she says, in many parts of the country traditional healers “are the people who are managing patients.” Recruiting healers to work with KEMRI’s research team has had hurdles, she says, such as fear that KEMRI might take what it learns from them and use it to design commercial treatments that could replace their offerings. KEMRI has developed steps to ensure that information learned from the healers is protected and to communicate this clearly to the healers. “We don’t want them to feel like they are losing the knowledge to us,” says Matu-Macharia.

In fact, KEMRI says working with it brings benefits, such as confirming that remedies are effective and safe, and offering suggestions on how to improve individual remedies. All of these should improve the trade for the healers. KEMRI does not give a seal of approval for products that perform well in tests it conducts. Healers and herbalists have to ask the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB), which regulates drugs in the country, to register their products. The PPB conducts more tests and analysis. Both also need also need a license from Kenya’s Department of Culture and Heritage.

One healer who has partnered with KEMRI is Munyiri Kahiu, a certified naturopath with 25 years of experience. Kahiu says he has used herbal remedies to successfully treat about 20 patients at different stages of diabetes. He also gives them customized diet and exercise programs. Kahiu says for the three-month treatment, his clients pay on average about 13,000 shillings ($100), similar to a month’s course of insulin. KEMRI validated his treatment as safe and effective.

The missing piece: a policy framework

KEMRI has developed research protocols to establish the effectiveness, safety, and quality of traditional remedies for diabetes, but KEMRI lacks the funding and legal frameworks to make them widely available. “The communities are using them now, but we cannot scale them up to commercializable products,” says Matu-Macharia. Despite the rise in cases, across Africa only one percent of health expenditure goes to diabetes care, the lowest investment rate in the world.

Nevertheless, some healers in Kenya have been able to commercialize their treatments.

When Fridah Muthomi was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, she found the cost of insulin and hospital check-ups too costly. In part, this was because she did not have a refrigerator and had to pay for cotton wool and surgical spirits to try to keep the insulin cold.

Her father, Moses Muthomi, is an herbalist in Nairobi. In 2015, he obtained approval from the Department of Culture and Heritage for a diabetes treatment he had researched and tested with help from Kenyatta University. Five years later, he expanded his work on herbal remedies for both communicable and non-communicable diseases, working with the University of Eldoret (both institutions are KEMRI partners). Muthomi has developed five herbal remedies, that address the effects of diabetes on the endocrine system and glucagon levels.

The products cost between 3,900 shillings ($30) and 10,060 shillings ($78) for a 48-day course of treatment. “I have so far successfully treated around 100 people who had diabetes,” says Moses Muthomi, including his daughter. She was able to stop using insulin two years ago.

Traditional healers like Muthomi say that once they get their products validated and go through the other approval processes to sell them, policy gaps are their biggest challenge. In Kenya, conventional doctors are only trained in Western medicine—and without formal government policies, doctors do not have the capacity to prescribe traditional medicines. Matu-Macharia agrees that Kenya lacks a framework for integrating traditional remedies into its health policies. “Even when we come up with products from the laboratory, it is not possible to integrate them because we don’t have legal frameworks in place,” she says. She is optimistic that the Ministry of Health, after 30 years, is close to having updated policy recommendations not only for diabetes treatment but for other conditions too. Duya cautions, though, that this is “still work in progress.”

The U.N. Foundation’s Ouma says he is hopeful Kenya will put forth regulations incorporating traditional knowledge, as it would help address public health safety concerns and boost access to treatment. Kiplangat, the former public health official, says his experience has made him wish that the policy framework would be updated so traditional approaches could be part of the public health toolkit. “Conventional medicine was not assisting me,” he says. “I hope that more people could turn to herbal medicine to manage their condition.”