Feature

The age of trauma

In 2014, Bizu Gelaye began to wonder what his life was worth to the country he lived in.

The associate professor of epidemiology at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health was watching from his Boston office as the Ebola virus killed thousands of people in West Africa. At the same time, in Ferguson, Missouri, activists were being gassed in the street as they protested the death of just one young man—Michael Brown—at the hands of the police.

Yet neither story seemed to matter much to Americans outside the crises.

“The world wasn’t paying attention,” Gelaye recalls. “Institutions were going on with their daily business as if nothing happened.”

As an Ethiopian immigrant to the U.S., as well as a student of disasters, Gelaye experienced both situations—and the general indifference to the fates of people who looked like him—as more than simple news stories. They were sources of emotional stress, a mental pressure he was constantly aware of.

Then, last summer, it happened again. As COVID-19 was devastating communities of color and videos of police killings were going viral, it seemed that many Americans—including the president—were unconcerned. “Living through the lynching of George Floyd and having another pandemic—it felt like “Groundhog Day,” Gelaye says, and the emotional stress that was so acute in 2014 bubbled back up.

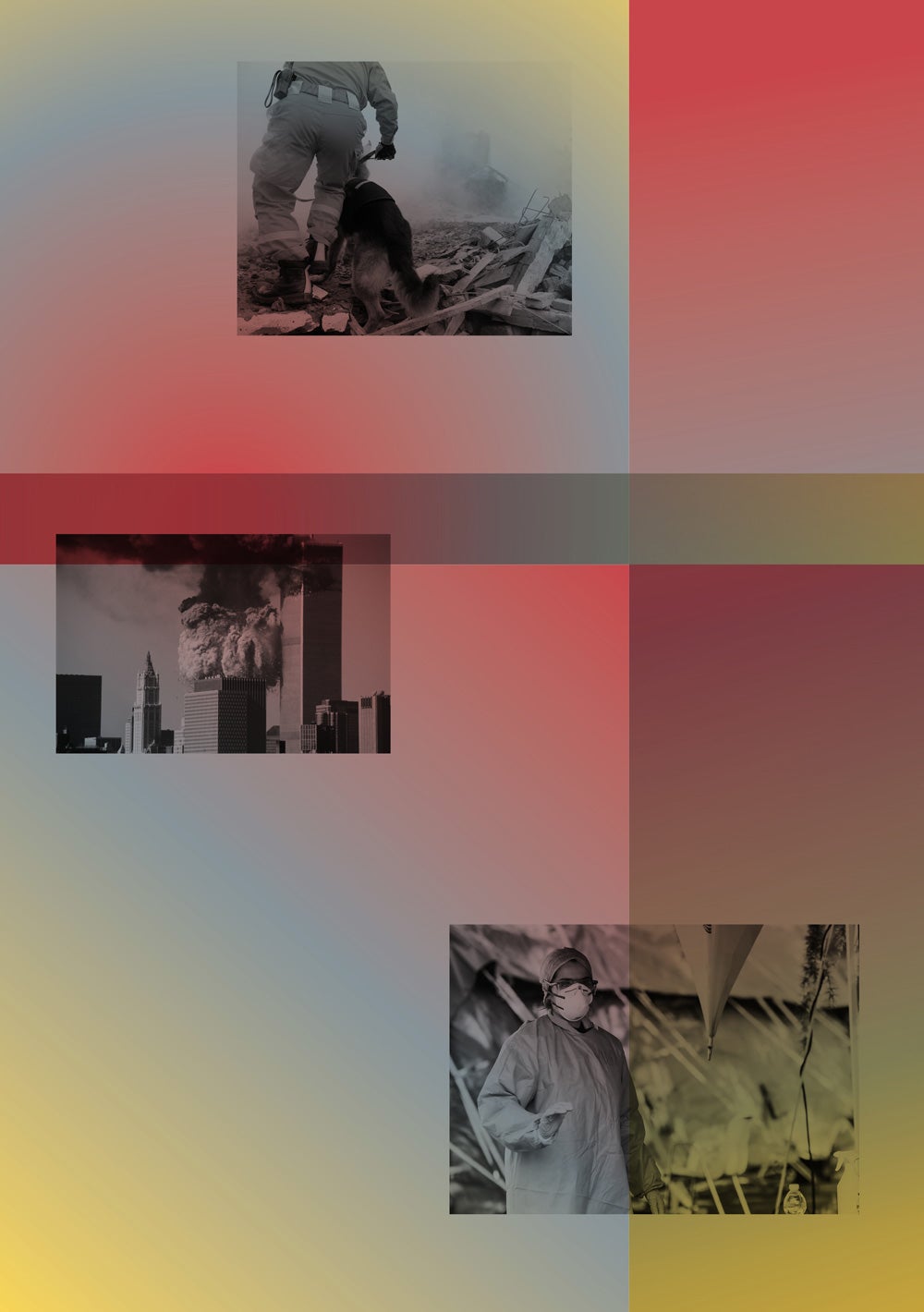

The burden of trauma

For Gelaye and countless other Americans, the last five or six years have been nothing if not traumatic—and in ways that overlapped, piled up, and influenced each other. We’ve experienced a divisive and volatile presidential administration; a pandemic that has killed more than 4 million people globally and overwhelmed health systems; historic surges in unemployment and poverty; and a national reckoning on racism, driven by the rise of hate groups and horrific videos of police violence—all of this backgrounded by an ongoing opioid crisis and increasingly destructive omens of climate change.

In short, we’re living through an age of trauma, and it’s taking its toll. Over the course of 2020, about four in 10 adults reported symptoms of anxiety and depression, according to a recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation—up from one in 10 in 2019. Other studies have put the rate of people experiencing traumatic stress at about a third of the population. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that 25 percent of U.S. adults reported psychosocial stress associated with fears of getting ill from COVID or infecting others, while 28 percent attributed feelings of isolation or loneliness as their source of stress.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Gelaye knows better than most that this onslaught of traumatic events could have disastrous implications for public health. The pervasive nature of COVID is such that everyone from the veteran emergency room doctor to the high school student stocking shelves at the grocery store is facing new challenges and fears, on top of whatever stressors and hardships they were already navigating. Gelaye’s own research has focused on teasing out the nature of how different traumas can exacerbate each other and worsen health outcomes, especially among vulnerable populations. “Disease and risk factors are not randomly distributed in our society,” he says.

This has been painfully obvious throughout COVID. The virus’s disproportionate impact on communities of color is attributable not only to economic disparities but also to the deleterious physical effects of racial trauma and “toxic stress”—as Gelaye and colleagues wrote in a recently published paper. “Direct injury, communicable diseases, child health, mental health outcomes—there is nothing that trauma doesn’t affect,” Gelaye says.

“Historically, the way we have defined trauma was not through a lens that accounted for racism.”

Bizu Gelaye,associate professor of epidemiology

Bizu Gelaye, associate professor of epidemiology

Photo by Kent Dayton

Experts, pundits, and activists have warned about a post-COVID wave of mental illness and have been advocating for increased mental health screenings and clinical interventions. A decade or so ago, those might have been seen as the gold standard in responding to the aftermath of a crisis of these proportions. But there’s now growing consensus among public health experts that screenings and treatments aren’t enough. In recent years, many researchers have come to recognize that any lasting remedy will have to encompass changes that are deeper, broader, more difficult, and more sustainable than simply treating immediate trauma.

“If people are aggrieved, then the reason for that needs to be removed,” says Shekhar Saxena, professor of the practice of global mental health and a former director of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse at the World Health Organization (WHO). “If people are not getting a fair deal at work or are in an unhealthy environment at home or in their community, then those conditions need to be improved.”

If injustice can cause trauma, and trauma can magnify the effects of disease, it stands to reason that any serious attempt at addressing the current mental health crisis—or the next pandemic for that matter—will hinge on a more just society. That’s a huge undertaking in a nation where our public support systems and services are often in dire straits and where economic disparity and political divisiveness have increased seemingly exponentially in the past decade.

But Saxena insists there’s no way around it. “Containing trauma is a task that is for the whole of society, not just for mental health professionals,” he says, “and that is something communities and countries need to realize.”

Now the question is, can we rise to the occasion? Or will the burden of trauma create a feedback loop that will make us sicker, poorer, and less ready for the crises to come

Age of syndemics

When we talk about trauma, we’re not necessarily discussing clinical post-traumatic stress disorders or other clinical disorders like depression. Gelaye broadly defines trauma as “an emotional response to a terrible situation that overwhelms an individual’s ability to cope.”

Mass traumas like COVID can push just about everyone a little closer to their breaking point: Those who had been doing well might struggle, those who had been struggling might be overwhelmed, and those who had already been in crisis might have a slimmer chance at recovery. When the pandemic arrived and the country closed down, many were already in the second and third categories—either because of other health conditions or because of life conditions. For them, COVID meant having to deal with simultaneous catastrophes, each intensifying the other. The home health aide whose immigration status makes her a target for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; the restaurant employee with a disabled kid; the family displaced by wildfires only to face racist attacks in a new town—to paraphrase Tolstoy, each trauma victim is traumatized in their own way.

“There’s been a term that’s been put out there that we’re dealing with,” says Giuseppe Raviola, director of mental health at Partners In Health and an assistant professor of psychiatry, global health, and social medicine at Harvard Medical School. “The word that’s been used is a ‘syndemic,’ as in multiple pandemics.”

The syn in “syndemic” stands for synergistic because each source of stress and trauma compounds and feeds off one another. Syndemic theory emerged in the 1990s as AIDS researchers examined how social ills and medical illnesses collided. The term was coined by Merrill Singer, a medical anthropologist at the University of Connecticut, who had observed that marginalized communities were always hardest hit by novel infectious diseases and seemed to always have a high incidence of what we now refer to as “preexisting conditions.” Singer recognized that this was no coincidence.

There are two dimensions to syndemic theory: the first, biological, the second, sociological. COVID, Singer says, is “one of the most impactful syndemics hitting the planet.” And while it is important to look at how preexisting conditions interact with the virus, it is equally important to look at the social and political factors that determine how those preexisting conditions are distributed. Through that lens, it’s clear that the same virus can have very different effects—both physical and psychological—on different populations. “There is no one COVID syndemic,” Singer says. “There are multiple COVID syndemics in different places based on local conditions.”

The effects of racism

At the start of the pandemic, as the country shut down, Monnica Williams was worried about the future of her mental health clinic, which in part caters to professionals, especially Black professionals coping with racism in their careers. Patients were canceling their appointments left and right, and some of her colleagues weren’t sure how they’d stay afloat. But within a couple of weeks, patients were calling back and booking virtual appointments. Since then, the clinic has been inundated with existing and new patients and has had to hire four new therapists to keep up with demand.

“I’ve definitely seen people’s mental health taking a nosedive over the last year,” says Williams, who is a clinical psychologist as well as the director of the Laboratory for Culture & Mental Health Disparities at the University of Ottawa in the School of Psychology.

Many of the people calling her for help were worried about exposure to the virus. But COVID wasn’t the only source of new stress. She was hearing from patients mired in the many stressors of a syndemic, including dealing with microaggressions from co-workers, racist rhetoric from elected officials, and the threat of abuse from law enforcement.

“The videos of police violence on social media and news broadcasts are traumatizing in and of themselves,” Williams says. “If you’re a member of those communities that are victimized, they’re hard to see replayed over and over again.”

For many people of color, racism is an ever-present component of their syndemic experiences. Yet racism has largely been overlooked for decades in the clinical mainstream as a health issue or as a source of trauma. Researchers such as the Harvard Chan School’s David Williams have made important contributions to establishing the associations between racism and poor health outcomes, but our health systems and policies have been slow to catch on. Consider that an analysis led by Nancy Krieger, professor of social epidemiology, looked at more than 200,000 articles published over the last 30 years in leading journals—the New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, the Journal of the American Medical Association, and the British Medical Journal—and found that less than 1 percent included the word “racism” anywhere in the text. And it was only this past April that the CDC’s director, Rochelle Walensky, publicly identified racism as a “major health threat.”

Monnica Williams has focused her research efforts on race-based trauma. In a recently published paper assessing PTSD in ethnic and racial minorities, she argued that experiencing racism should be recognized as a traumatic event. “We see higher rates of PTSD in Black communities, and I’m sure a lot of that is due to racial trauma,” Williams says. “It’s almost impossible to be Black in America without some racial stress, and over a certain threshold, racial stress becomes racial trauma.”

Throughout the pandemic, Williams has been especially in demand as a clinician of color, an underrepresented minority in the mental health field. The lack of diversity in the psychology workforce is stunning: According to the American Psychological Association, only 4 percent of psychologists in the U.S. workforce are Black or African American, while 86 percent are white. The lack of nonwhite therapists is a huge structural barrier to care and one of the reasons communities of color underutilize mental health services, contends Gelaye. “People are not going to feel comfortable discussing trauma events related to racism if they don’t see someone who looks like them,” he says.

Gelaye has explored how this kind of chronic, untreated racial trauma can actually cause neurophysiological changes that make it harder for individuals to fight off viral infections like COVID. As Gelaye recently noted in a research paper, part of the disproportionate impact of the COVID pandemic on Blacks and other communities of color can be traced to structural factors that reduce the practice of physical distancing, disallow the opportunity to work from home, or impair the ability to obtain proper health care and nutrition. He added, however, that another hallmark of the COVID pandemic is that the hardest hit in terms of morbidity and mortality appear to be those suffering from metabolic diseases related to stress.

What that means, Gelaye says, is that “the daily insults, the indignities, the demeaning messages that people of color experience lead to outcomes that have a devastating impact on individuals’ health.” It can be difficult to study these effects, he says, because, as Krieger’s research made clear, the body of scholarship investigating the health effects of racism is limited. “Historically, the way we have defined trauma was not through a lens that accounted for racism,” he says.

When it comes to treating racial trauma, helping individuals address their experiences, like Williams does in her practice, is important. But ultimately, any effective public health response has to include structural change to remove the source of the trauma.

“If we address at the level of society some of the root causes, we would be able to make a meaningful difference in attenuating the impacts,” Gelaye says.

Williams agrees. “I don’t want to keep fixing people with racial trauma, I want to get rid of racism,” she says. “The bigger, more important goal is for us to have social justice and equity in every aspect of society.”

Unhealthy health care workers

In many ways, COVID is a great equalizer in terms of making bad situations worse. Take health care workers, many of whom were seriously struggling with burnout long before the pandemic. “COVID has clarified the vulnerability of health care workers,” Raviola says. “The solutions are significantly systemic, not just clinical. People can’t be pathologized excessively to circumvent our common responsibility for taking care of health care workers.”

In 2019, the Massachusetts Medical Society, the Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association, the Harvard Chan School, and Harvard Global Health Institute issued a report identifying burnout among health care workers as a public health crisis. The report noted that a staggering 78 percent of physicians surveyed said they experience some symptoms of professional burnout, defined as a syndrome involving one or more instances of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished sense of personal accomplishment. A follow-up op-ed in the Boston Globe co-authored by Dean Michelle Williams and colleagues noted that the effects of burnout trickle through entire health systems. “We cannot improve patient experience and population health while reducing health care costs without a strong and engaged physician workforce,” the authors noted. Sources of burnout identified by the report included poorly designed digital health records and a lack of mental health treatment and support for caregivers. And this was all before COVID entered the lexicon.

The pandemic has thrown a spotlight on other vulnerabilities and sources of stress and trauma health care workers encounter. One reason this population is especially exposed is because, in addition to experiencing trauma directly, they vicariously witness others’ trauma. It’s especially true among mental health professionals. A recent study of 339 psychotherapists in the U.S. found that many were experiencing symptoms of trauma just from treating clients who were traumatized by the pandemic: A third reported feeling less confident in their work than before the pandemic began, and half said they were having more trouble connecting emotionally with their patients.

Indeed, Monnica Williams says she often counsels other counselors. “I get a lot of calls from other therapists of color who are exhausted and stressed themselves, taking care of so many people,” she says. “They can carry so many people, but no one is carrying them.”

That goes for other medical professionals, too.

In 2018, Simon Talbot of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Wendy Dean of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine described physician burnout as “moral injury”—a term originally used to describe the psychic wounds of Vietnam veterans and civilian survivors of war. Moral injury has been defined as the trauma of “perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”

In health care workers, Talbot and Dean wrote, moral injury was the result of “being unable to provide high-quality care and healing” to patients in an “increasingly business-oriented and profit-driven health care environment.” Without systemic changes, they warned, the problem would only worsen. “The increasingly complex web of providers’ highly conflicted allegiances—to patients, to self, and to employers … may be driving the health care ecosystem to a tipping point.”

That tipping point was plain to see as health care workers found themselves making impossible choices treating COVID patients for whom there were not enough resources to go around. So, it’s no surprise that a recent study found that roughly half of American health care workers surveyed were at risk for trauma-related mental health issues. Another study of mental health care workers had even more alarming results: 93 percent of survey respondents reported symptoms of stress and trauma.

It’s not always easy to get medical workers to avail themselves of therapy, either, says Raviola, who worked to build a wellness and peer support program into Massachusetts’ COVID contact tracing project. Therapy “is not necessarily something that’s emphasized within the medical profession,” he says.

Moreover, Raviola adds, sending individual physicians to therapy can seem like an underwhelming response to a structural problem. “It gives the impression of an easy fix to a complicated problem—the solutions are significantly systemic, not just clinical.”

Tackling root causes

The concept of moral injury may date back to the Vietnam War, but the concept of trauma itself was born in World War I, when PTSD was first described as “shell shock.” That was the first time mental health was considered as part of the burden of war or disaster. Progress toward recognizing the problem and treating it, however, has been slow. Even by the end of the 20th century, mental health wasn’t much discussed as part of international relief efforts for natural catastrophes or armed conflicts, Saxena says.

“More and more, we are seeing approaches to mental health aimed at removing the distress that people have while also removing the causes for the distress.”

Shekhar Saxena, professor of the practice of global mental health

Shekhar Saxena, professor of the practice of global mental health

Photo by Kent Dayton

“In the case of a flood, for example, humanitarian agencies were much more worried about the people who had drowned, how to dispose of bodies, how to prevent an outbreak of a waterborne disease,” he says. “Mental health was often not even on the table.” And when mental health services were offered after traumatic events, Saxena explains, they were often crude, lacking an evidence base, and sometimes clearly harmful. As an example, he points to a technique known as “psychological debriefing,” which was popular in the 1980s and 1990s and even deployed after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It prescribed a kind of emergency talk therapy to stave off PTSD: a single session in which subjects were asked to recount their traumatic experience so they could “process” it safely. But studies eventually established that this process could actually cause harm. “If you ask people to recount and in some way relive the trauma, they may become more traumatized,” Saxena says.

In 2003, Saxena’s Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse at WHO produced a guide to supporting mental health in “populations exposed to extreme stressors.” It advised culturally appropriate psychological first aid followed by “medium- and long-term development of community-based and primary mental health care services and social interventions.” It specifically advised against deploying psychological debriefings.

For Saxena and other mental health professionals, the publication of the WHO report marked an important step forward for the field and for victims of traumatic experiences. “The consequences of that document were that when governments and nongovernmental organizations started putting resources into emergency health care and humanitarian assistance, mental health was on their radar and no longer overlooked or forgotten,” he says.

The WHO’s approach to mental health has evolved significantly over the years. “In the beginning, we needed to demonstrate that mental health and psychosocial consequences of traumatic events are there and important to pay attention to,” Saxena says. The original WHO guide focused on delivering clinical treatment to those who needed it; the words “justice” and “disparity” do not appear. But during his two-decade tenure at WHO, Saxena says, he often found himself advising various ministries of health that the best thing they could do for the mental health of their population was to improve the actual circumstances in which they lived.

“If there is violence, the best thing is to reduce the level of violence. If discrimination is built into the laws of society, those need to be reduced by whatever means possible,” he says. The same for poverty, joblessness, and other sources of stress.

There has been a clear shift toward root-cause thinking among health professionals who are tasked with treating and mitigating trauma. A recent paper in Lancet Psychiatry co-authored by an international consortium of researchers explored how mental health care should change in the wake of COVID. The paper included a conversation on “ethics-driven and rights-driven considerations” and emphasized the need to address the “underlying social drivers of inequality.”

It’s a good example of how discussions about mental health care in the wake of disaster have changed. “The field has matured,” Saxena says. “More and more, we are seeing approaches to mental health aimed at removing the distress that people have while also removing the causes for the distress.”

The path forward

The cascade of traumas is by its nature overwhelming to individuals, to health systems, and society at large. Just making sure that everyone who needs psychological first aid can access it is a huge project, given the siloed nature of American health care. How can we triage mental health needs while simultaneously solving other structural problems—racism, violence, economic inequality, political upheaval? It seems more than daunting.

But that’s only one way to think about it. Another way is to recognize that whenever we tackle those other problems, we’re simultaneously addressing mental health problems. By removing sources of trauma, we’re making our societies more survivable and resilient.

In a way, this is what the best public health practitioners have always done to improve the well-being of towns, cities, and countries. Nineteenth-century physician John Snow knew it was important to treat cholera patients, but he also made clear that it was critical to fix London’s woeful wastewater infrastructure. When drugs to treat AIDS were still being tested, activists also fought to improve living conditions, remove oppressive laws, and spread awareness about safe sex. Every public health initiative is biological and sociological—because we humans are both things.

While the COVID pandemic has been a historic source of stress and trauma for millions of people, it’s also sparked long overdue conversations about the other ills of society and the need to confront them. Now it’s time to turn conversations into interventions.

Saxena uses the analogy of a highway where the curve of the road causes a lot of accidents. There are different ways to deal with the problem: You could station an ambulance there or put a phone nearby so people can call for help after they crash.

“But the correct solution,” he says, “is that you actually modify the highway in such a way that accidents don’t occur.”

S.I Rosenbaum is a freelance writer whose reporting has appeared in New York, the Boston Globe, and Boston Magazine, among many others.