Feature

The new market for public health entrepreneurs

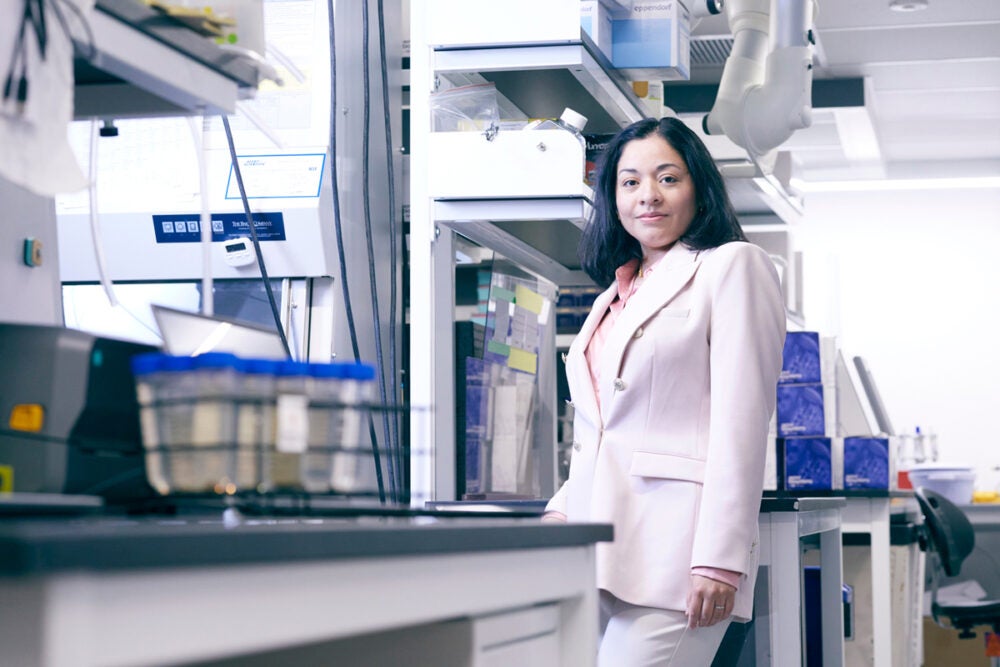

In 2017, when MIT graduate students Mariana Matus and Newsha Ghaeli founded a company based on their research into using wastewater metrics to inform public health, they didn’t realize just how hard it would be to raise money.

Their work used a robot to collect sewage samples and analyze them for indicators such as illicit drug use and germ concentrations. They saw public health departments as a ready market for their company, Biobot Analytics. But their vision of a mission-driven company that helped local governments foster healthier communities proved hard to fund. Matus says venture capitalists “just aren’t as comfortable with having the government as the customer.”

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

She says Biobot repeatedly got the same feedback from potential investors: Create a nonprofit, get academic grants, and do good that way. “We were determined that we could build a company that could…do good and make money,” Matus, Biobot’s CEO, says. Even when in 2018 it got into Y Combinator, possibly Silicon Valley’s premier accelerator program (see Pushing the startup accelerator), VCs weren’t willing to open their wallets, perhaps because fewer than 1 percent of Y Combinator companies develop health care diagnostics.

Mariana Matus, co-founder and CEO of Biobot Analytics, which grew out of her PhD work at MIT in computational biology.

What the Biobot founders experienced was typical, says Jenny Yip, a managing partner at public health venture capital firm Adjuvant Capital. A decade ago, if you focused on “impact investing,” counting a beneficial effect on society as part of the return, “it was assumed that we weren’t going to make any money,” Yip says. “That was the trade-off. It was doubtful you could impact climate change, health care, or other fields, and have a healthy financial return.”

The pandemic appears to be changing that, fueling a new breed of public health entrepreneurs and interest from venture capitalists who see ways to apply market forces to address problems, such as the need for better diagnostics tools. One sign of the shift comes from the diabetes-monitoring and management technology company Vizzhy, which just won the Accelerate portion of MIT’s $100K Entrepreneurship Competition. “On the funding and financing side, many investors wouldn’t have known about diagnostics or POC (point of contact) or so many other public health terms before COVID-19,” says Yip. “There is a nuance and an increased focus on funding public health.”

Virtual event

From idea to impact: The new market for public health entrepreneurs

In the first half of 2021, global VCs invested $15 billion in digital health companies, including telemedicine, wellness, and public health, according to Mercom Capital Group. That capital eclipsed the $6.3 billion raised in the first half of 2020 by 138 percent. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has even gotten involved, launching a $50 million venture capital partnership to invest in public health start-ups creating better responses to, or helping prevent, emergencies and other national security threats. Vinit Nijhawan, managing director of MassVentures, the venture capital firm of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, believes public health funding will follow a path similar to biotech, where university research is regularly used to create start-ups. “Private capital is seeking university spinouts to invest in, particularly with the sciences,” he says. “Investors are looking for the next big leap.”

The pandemic certainly created a bounce for Biobot. While it had successful pilots on opioid detection in Cary, North Carolina, and several Massachusetts areas, the sales cycle was slow. Within weeks of broad shutdowns in March 2020, Biobot began piloting SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in its products. By May 2021 it got its first contract with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and in October 2021 it raised $20 million in funding to expand its data platform. Last fall it relaunched its opioid measurement tool as well as measurements for other high-risk substances, and influenza detection.

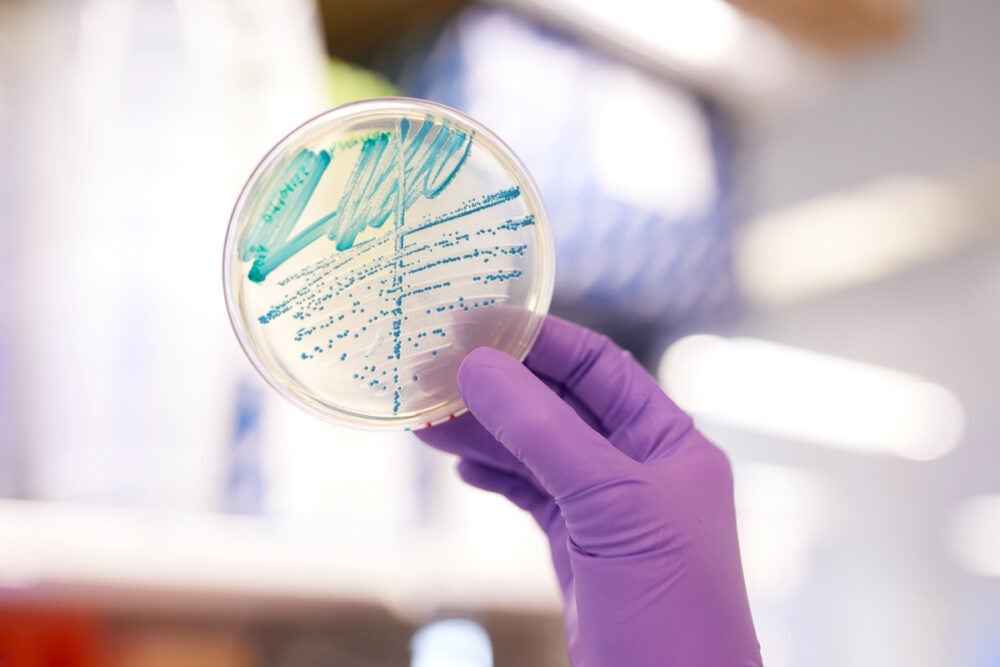

Public health startups still experience resistance from funders. “A lot of people want to invest in treatment, but public health is all about prevention. It’s not where the investors want to go because it isn’t as lucrative,” says Minmin Yen, co-founder of PhagePro, an early-stage biotechnology therapeutics company that is developing bacteriophages—viruses that kill bacteria and prevent them from causing disease.

Minmin Yen co-founded PhagePro using research she was doing at Tufts on preventing cholera. At right, an experiment in progress.

Yen’s company grew out of a cholera-focused practicum in Haiti she attended while doing academic research at Tufts University. The trip opened her mind to how access, poverty, and politics can muffle scientific impact. It also got her thinking about how her research could reach the people who needed it most. “Just because you do the lab work, that doesn’t mean someone is translating it” into a treatment, she says. She and co-founder Andrew Camilli decided founding a for-profit company would enhance their potential. For one thing, it gets them out of what Yen calls “the usual donor dynamic” of co-dependence between the giver and receiver of aid. It’s “almost like a savior complex,” she says.

The pandemic highlighted a gap between public health innovations in the lab and public health impact in the community. As a recent CDC peer-reviewed commentary notes, COVID is disproportionately affecting Black, Latino, Native American, and LGBTQ communities for two particular reasons: lack of trust in government systems providing care and lack of access to the care itself. By connecting directly with the community—i.e., the market—public health entrepreneurs can potentially build a level of trust and understanding harder to achieve through a university or a large corporation. Matus says public health officials can benefit from the kind of help private companies can offer. “We researched many cities and … they are flying blind on how to make health decisions,” she says.

Not all public health entrepreneurs come out of science laboratories. Time magazine’s top 100 inventions of 2021 included vaccines for malaria and COVID as well as home testing kits, but also Clove sneakers, which makes “foot therapy” shoes targeted at health care workers, Bento, a food assistance text-messaging service, and the Emme birth control management system. Then there’s incrEDIBLE eats, which markets edible cutlery. The goal, says co-founder Dinesh Tadepalli, is to reduce plastic waste. “Humans take in a credit-card-sized amount of plastic hidden within their food, air, and water every week. We have no clue about how it affects our bodies,” Tadepalli says. In 2019, while still working as a semiconductor engineer at Intel, he started developing edible spoons. He went to a food trade conference in New Orleans, pitched his wares, and got an order for 150,000 spoons. To get seed money to fill the order, he and his wife sold their house in Silicon Valley, relocating to Morrisville, North Carolina. Since then, incrEDIBLE eats has negotiated a partnership with the maker of the amusement park ice cream staple Dippin’ Dots and prevented the use of 3 million plastic spoons.

Dinesh Tadepalli pitching incrEDIBLE eats on Shark Tank.

Photo courtesy of Dinesh Tadepalli / incrEDIBLE eats

Edible cutlery being produced.

Photo courtesy of Dinesh Tadepalli / incrEDIBLE eats

IncrEDIBLE eats is largely self-funded by Tadepalli and engineer co-founder Kruvil Patel, but Tadepalli did appear on the televison show Shark Tank last fall, and got one of the sharks to bite—$500,000 in exchange for 15 percent of incrEDIBLE eats. Though that deal fell through, Tadepalli says the show helped generate substantial interest in his company’s cutlery.

Yip says investors are learning how to create better financial returns from public health companies. “As someone who has been involved in the sector for years, this makes me very happy to see.” For Matus, the payoff is clear. Biobot’s venture funding helps it attract talent—it’s been on a hiring spree and has nearly 70 employees—and gives it “tailwinds to grow faster,” she says. It has been, for her, the culmination of a near-lifelong goal that started forming when she was growing up in Mexico City. “I was near the slums and directly saw the effect of pollution, bad public service, and bad health,” she says. Finding answers to some of these problems drew her into science, but she knows that running a lab would not have the direct impact on public health she’s been able to have with her business.