Book

“Wonder Drug” draws back the veil on thalidomide’s hidden American victims

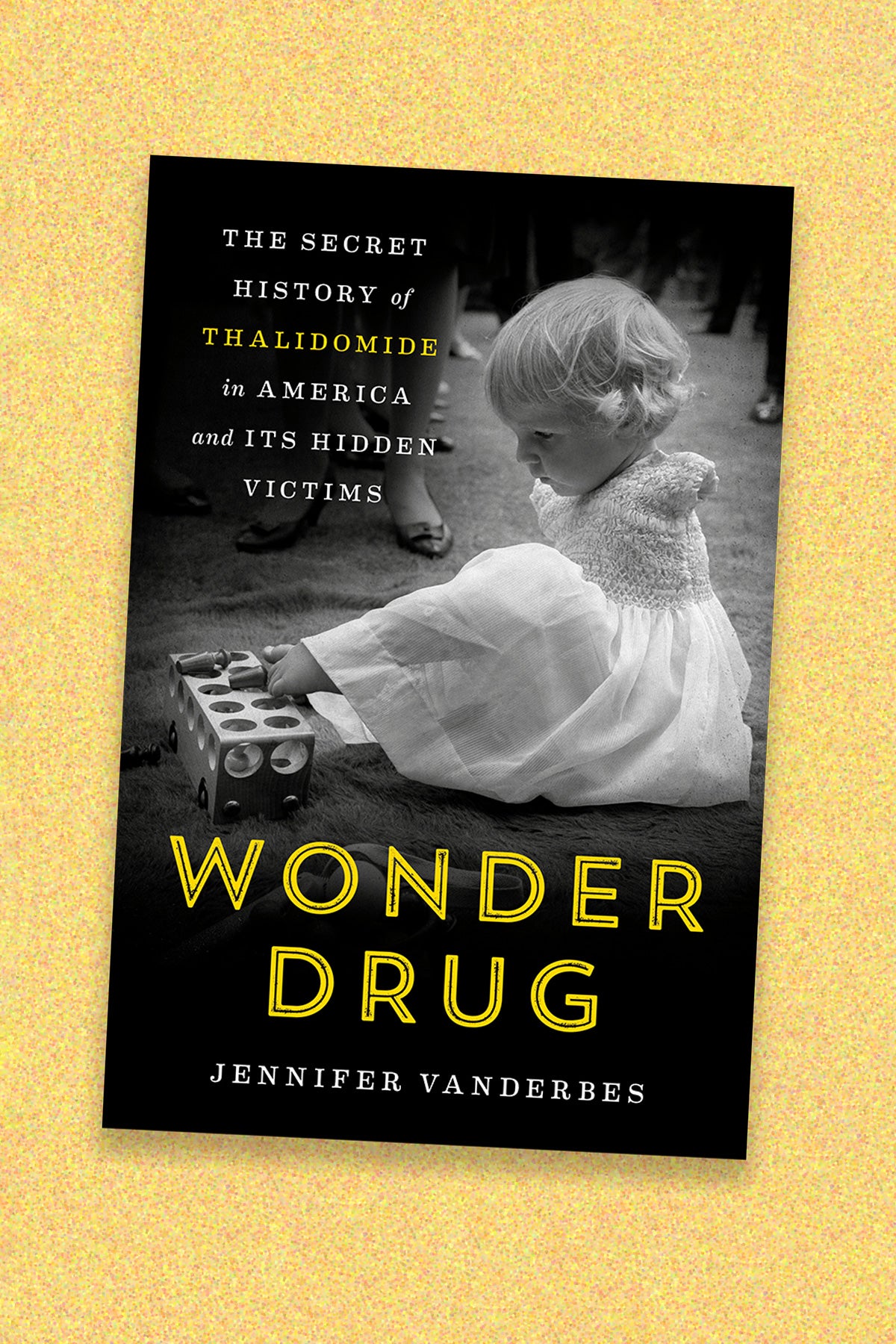

Wonder Drug: The Secret History of Thalidomide in America and Its Hidden Victims, by Jennifer Vanderbes

If Americans remember the tragedy of thalidomide, it’s as a story of the FDA and some courageous investigative reporters saving the United States from a public health disaster. The U.S. never approved the drug, which killed perhaps 10,000 children in Europe and caused thousands more to be born with serious birth defects. What really took place in the U.S. in the early 1960s was much more harrowing than we remember, as Jennifer Vanderbes makes clear in her riveting new book Wonder Drug: The Secret History of Thalidomide in America and Its Hidden Victims.

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

The wonder of thalidomide, created by West German drugmaker Gruenthal, was its initial claims to be an effective sedative without side effects. But the drug had undergone only minimal testing, and when it was given to pregnant women to counter morning sickness, many of them lost their babies or gave birth to severely deformed infants.

The FDA does merit credit, thanks mostly to Frances Kelsey, an FDA examiner working on her first new drug application. She made a heroic stand to prevent U.S. approval of thalidomide, for which she was celebrated in the Washington Post and received a presidential medal from John F. Kennedy. Unfortunately, the agency as a whole did not measure up to Kelsey’s standard. In fact, FDA leaders and managers put their heads in the sand about how widely available thalidomide had been in the U.S. even without approval. This was a disaster in its own right, one the FDA repeatedly bungled its investigation of. To this day the agency’s official position is that only six surviving American children were maimed by thalidomide. The true figure is almost surely dozens, with scores of other miscarriages and stillbirths.

The U.S. distributor, Merrell, part of what became Richardson Vicks, had skipped animal testing of thalidomide altogether. Instead, Merrell distributed millions of pills to tens of thousands of Americans through “clinical trials”—free handouts offered by more than a thousand doctors, in varying dosages, formulations and colors, for which almost no records were kept. Ground zero in the U.S. was the company’s own hometown of Cincinnati. Merrell then stalled on reporting adverse effects, first peripheral neuritis (nerve disease that affects the body’s motor and sensory systems), then phocomelia (shortened limbs), and tried repeatedly to muscle past Kelsey.

To this day the [FDA]’s official position is that only six surviving American children were maimed by thalidomide. The true figure is almost surely dozens, with scores of other miscarriages and stillbirths.

The press was, by turns, both courageous and indifferent. In West Germany, where the drug was invented, a report in the newspaper Welt am Sonntag brought a halt to the thalidomide nightmare in the country where it began, and the Sunday Times of London eventually earned some recompense for British victims. But the New York Times reporter in Germany passed on the story, as did Redbook, which didn’t want to scare expectant mothers. Stories in Time and the Washington Post weren’t followed up in their newsrooms, and were ignored by the rest of the press. Life magazine horrified Americans with photos of the European victims but also excused inexcusable conduct by the German, U.S. and British drug companies involved.

The drugmakers depicted here are almost living caricatures of evil pharma companies. Gruenthal employed actual Nazis—one of thalidomide’s key developers had experimented on prisoners at Auschwitz and Buchenwald, killing hundreds. At one point Vanderbes openly wonders if thalidomide was first formulated in the camps. The company did not do serious testing yet hailed the drug as safe for everyone. Thousands of dead or deformed babies resulted in a German criminal case against Gruenthal, which ended without a conclusion in 1970. Nearly 40 years later, the company apologized to roughly 5,000 surviving German victims, but paid them settlements that seem shockingly low.

The companies wilfully minimized evidence that the drug had serious side effects, and continued to push it into new markets, creating an early example of the true globalization of health issues. Ultimately, thalidomide harmed children in perhaps 45 countries, with some failing to compensate victims until this century. The U.S. government still has not done so.

Vanderbes, previously a novelist, tells her story with verve, power, and empathy, adding weight by interpolating the stories of victims throughout, and coming back to them at length toward the book’s conclusion. A few brave parents and many determined survivors get a voice here. Vanderbes celebrates Dr. Kelsey and two other female medical pioneers, Dr. Barbara Moulton and Dr. Helen Taussig, who helped end the thalidomide nightmare and spur drug approval reform in the U.S. But this story leaves readers with no illusions about the limits of what was accomplished at the time, or has been acknowledged since.

Wonder Drug | By Jennifer Vanderbes | 432 pp. | Random House | $28.99

Book cover: Courtesy of Random House Group