Opinion

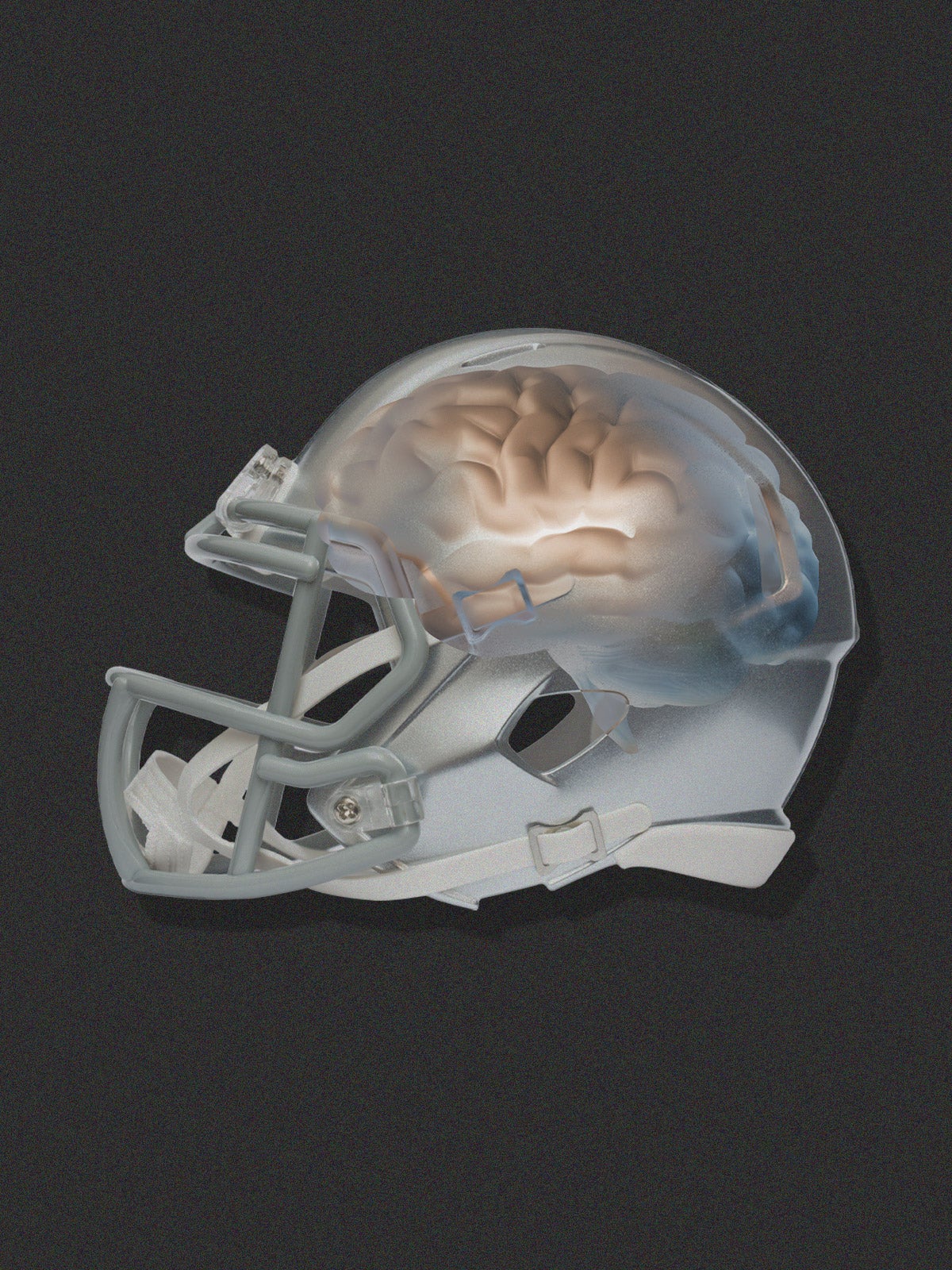

There’s a way to deal with brain injuries in football. It isn’t safety gear.

As the Kansas City Chiefs and the Philadelphia Eagles prepare for Super Bowl LIX, the National Football League (NFL) is spreading the good news: Concussions are down. But don’t be fooled—concussions and traumatic brain injury are still a major problem in football.

Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa’s third concussion last September elicited calls for his retirement. Weeks later, Hall of Famer Brett Favre revealed that he has Parkinson’s disease due to the many concussions he believes he sustained while playing.

Concussions are mild traumatic brain injuries that can result in a constellation of physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms. Since 2015, NFL players have logged more than 2,200 concussions in practices and games. It’s harder to get clear numbers in youth football, but we know that each young player sustains about 375 head impacts per season.

Despite the growing concern around concussions and their long-term impact, about 1,700 active NFL players, about 81,000 college students, and two million local youth play football each year.

What will protect these athletes from brain injury and long-term consequences? According to the NFL and companies looking to profit, it’s new protective gear like the Guardian Cap. The problem is that some players, coaches, and football fans conflate the use of this and other gear with brain injury prevention—a feat no piece of equipment can currently achieve in tackle football.

Players are also not required to wear the protective gear. Tagovailoa announced he would not wear one, even after his third concussion.

Concussions in the NFL did decrease this year—182 concussions were diagnosed in NFL players, 17 percent fewer than last year. But football players still experience more concussions than any other athletes, and the risk will never be zero. Safety equipment also cannot prevent the damage associated with repeated head impacts.

CTE is caused by an accumulation of an abnormal protein in the brain from repeated head impacts. Research indicates that lower-grade head impacts are more strongly linked to the disease due to their frequency. CTE symptoms include aggression, memory impairment, and suicidal ideation.

About 90 percent of the 376 deceased former NFL players who donated their brains to Boston University’s CTE lab had CTE. A Harvard study of living former NFL players found that one-third believe they have the condition.

New gear is supposed to alleviate the CTE problem. The Guardian Cap fits over a football helmet and is meant to absorb and spread the force of a hit, purportedly by up to 25 percent. Since 2022, they have been mandated for some players during practices. In 2024, they were approved for use in the regular season.

But only an average of six players wore them each week in the NFL and the Canadian Football League combined, even though Guardian and the NFL claim that concussions are down by over 50 percent in the players who wear them during practice.

Perhaps the players are aware that at least three independent studies have shown that the caps make no difference. In one study of college football players, lab testing indicated that Guardian Caps reduced head acceleration and the force of impacts, but when the researchers replicated the testing on the field, the caps made no difference at all. Another lab-based study and a third, on-field study confirmed the first study’s field findings.

Also being marketed is the Q-Collar, a Food and Drug Administration-approved piece of equipment meant to minimize the brain’s movement inside the skull. Modeled after the anatomy of woodpeckers, it sits around the neck, applying pressure to the jugular veins to slow blood flow out of the head. Q-Collar creators say this increases blood around the brain, cushioning it and reducing its movement within the skull after impact.

The company that makes the Q-Collar doesn’t claim it prevents concussions and critics note that we don’t know if it actually protects the brain from future harm. And in 2022, scientists found that woodpeckers’ brains are protected from damage simply due to their size and orientation within their skulls.

Like the Guardian Cap, uptake of the Q-Collar among football players is low.

More helpful than the questionable effects of gear would be a better response to head trauma when it happens.

A good first step would be establishing standardized return-to-play protocols across all levels of football. The NFL’s five-step protocol that concussed players must follow before returning to practice doesn’t have guidelines for how long players must spend in each phase of recovery. Yet one study shows that adult men need about 25 days, and women about 35, to recover from a concussion. NFL players typically return to play nine days post-concussion.

Return-to-play protocols are overseen by team physicians who may feel pressure to quickly clear star athletes. Standards could prevent incidents like Tagovailoa’s 2022 event, when he sustained a concussion during a game and was cleared by team doctors to play four days later. He suffered a second concussion during that game and had to be hospitalized.

Other sports have clear rules about required rest. The Australian Football League mandates a 12- to 21-day rest period following concussion. The World Boxing Association requires at least a 60-day suspension for any boxer who gets knocked out from a hit to the head.

Oversight will be needed to make return-to-play protocols effective. Over one-third of American high schools don’t have athletic trainers. As a result, young athletes rely on teammates, coaches, or parents to recognize a concussion and seek appropriate treatment. Without professional support, and a mandated recovery window, many athletes may never seek care and return to play too quickly.

Of course, rest does not reduce the risk of head trauma once a player is back on the field. Whether you’re rooting for star quarterbacks Patrick Mahomes (two confirmed concussions in his career) or Jalen Hurts (concussion in December) this Sunday, know that they along with every player on the field face a hidden threat on every play.

The only sure way to prevent head injuries in football? Don’t play.

Source images: Adobe Stock, iStock