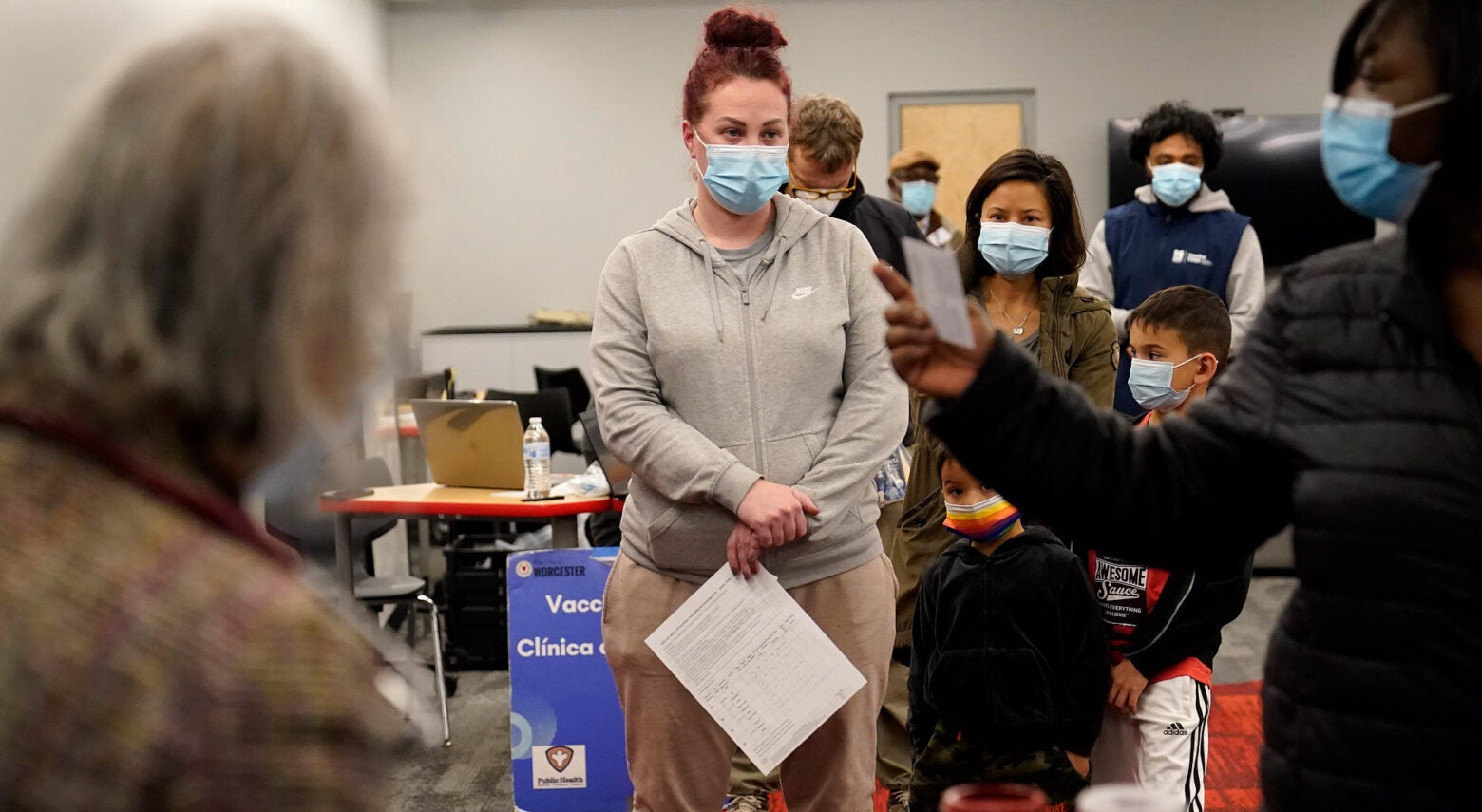

Leah Perkins, of Worcester, Mass., center, stands in line to receive a booster shot of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine, Dec. 2, 2021, at a mobile vaccination clinic, in Worcester. More U.S. states desperate to defend against COVID-19 are calling on the National Guard and other military personnel to assist virus-weary medical staffs at hospitals and other care centers. Steven Senne / AP Photo, File

Ideas

Massachusetts tackles flaws that cost lives during the pandemic

Massachusetts has a reputation for health care leadership and innovation in the United States, but in public health coordination, it has been a laggard. While most of the 50 states have long required public health workers to collaborate at county and regional levels, Massachusetts has not. During the COVID-19 pandemic, that meant widely varied responses across its 351 municipalities—resulting in many unnecessary deaths. “Your zip code largely determined your public health protections,” says Massachusetts State Sen. Jo Comerford. “Covid exposed gross inequities, and we were vulnerable as a commonwealth because of (them).”

The legislature moved to address these by passing the Statewide Accelerated Public Health for Every Community (SAPHE) Act, signed into law by Gov. Charlie Baker on April 29, 2020. Comerford co-sponsored SAPHE 2.0, which Gov. Maura Healey signed in December 2024. It provides funding for local health departments; allows for the creation of a new statewide data collection system and shared services; and requires the development of uniform credentialing systems for public health workers. The new law is “next-generation” public health legislation, says Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. He calls it “a model for other states seeking to provide the legislative basis for public health system improvement efforts.”

Sign up for Harvard Public Health

Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Harvard Public Health’s Maura Kelly conducted separate interviews with Comerford and with Oami Amarasingham, deputy director of Massachusetts Public Health Alliance, which helped develop SAPHE 2.0. The interviews were edited and condensed.

HPH: Why this legislation?

Comerford: There is a moral and ethical responsibility to ensure equitable services to all residents of the commonwealth. As a commonwealth, we are less strong if we have weak pockets of resilience. That weakness appeared not only where we have seen weak public health protection and public health inequities—immigrant communities, communities of color, low-income communities. We also saw real weakness in rural communities that did not have the infrastructure to launch a full-on response to the pandemic.

Amarasingham: Covid made the case clearly to every individual and to every elected official that public health infrastructure is really important. Local public health officials have been trying to solve the problem of a lack of public health infrastructure, staff, funding, and statewide minimum standards for decades. We have one state department of public health and 351 local departments of health, whereas most states have county- and regional-level departments. Each local health department has been funded by the town or municipality and many have pretty limited resources. The city of Boston has a really big public health department, but after that, every public health department is much smaller. In some places, public health departments are open a few hours a week.

HPH: Would this law have helped Massachusetts get through Covid better, with less loss of life?

Comerford: We have huge pockets without cell service here in western Massachusetts. We have almost no consistent internet service. We relied on unbelievably intrepid public health officials to go door to door [telling people about Covid, vaccines, testing, and so on]. At the time we weren’t logging our work in a way that was consistent and usable information. There were a lot of gaps in information sharing, which is terrible in a crisis. You can’t understand what you can’t measure and track. Now there has to be data collection, training, [and] the state has to help resource this.

Amarasingham: We were not in great shape to respond in the most effective, most equitable way. What public health officials had during Covid was a PDF [containing the latest statistics]. You needed someone to convert that to an Excel spreadsheet if you wanted to use the data. It was not useful for data scientists or anyone who wanted to produce something with that data. It didn’t track demographic data. When you have 351 separate entities reporting data, you want that data to be collected and compiled in a uniform way so that it can be combined and used. It was very frustrating not being able to quickly access and understand data in a rapidly evolving situation.

HPH: Public health workers and officials came under attack during Covid. Will this new law help to protect them?

Comerford: By having performance standards and requiring a credentialing process as indicated in the law, the state is raising the level of credibility associated with public health officials. They will now be better trained, better connected, better resourced. I hope that the workforce is much stronger as a result of this legislation.

HPH: MPHA helped to develop this legislation. Did you take any lessons from other states?

Amarasingham: We understand that other states have better systems for data collection. We are not talking about personal, identifiable data, [but, for instance,] how many food inspections have been done at restaurants, when, by whom, so that public health officials can have a full picture of who is responsible. The legislature appropriated nearly $100 million in ARPA [American Rescue Plan Act] funds to go towards building and maintaining a data system to integrate data collection between the local health departments and the state.

HPH: If there is a single public health challenge looming in the future for Massachusetts that this bill will help to mitigate, what is it?

Amarasingham: Almost anything you read about in the headlines has a local public health implication. So, for example, we’ve had these extreme weather events that dump a lot of water in a short period of time and overwhelm the sewer system—so then sewers get contaminated and it can be unsafe to swim on a beach or in a river. It can reach crisis level rapidly and you have to deal with it, and if you don’t have the public health infrastructure in place, then you are trying to build the infrastructure while addressing the crisis, which is what happened during Covid. And in a case like that, the toll on the human beings who work in these understaffed systems can be overwhelming, and they quit.

HPH: Did this bill pass at an especially timely moment?

Amarasingham: We know the health impacts of climate change are going to get worse. The spread of disease will get worse. [Add to that] the uncertainty of what will happen with the incoming administration—it is the right time. These challenges are bigger, they are unfolding more rapidly, and they are ongoing.

Comerford: The Office of Senator Jo Comerford

Amarasingham: Mario Quiroz / Courtesy of MPHA