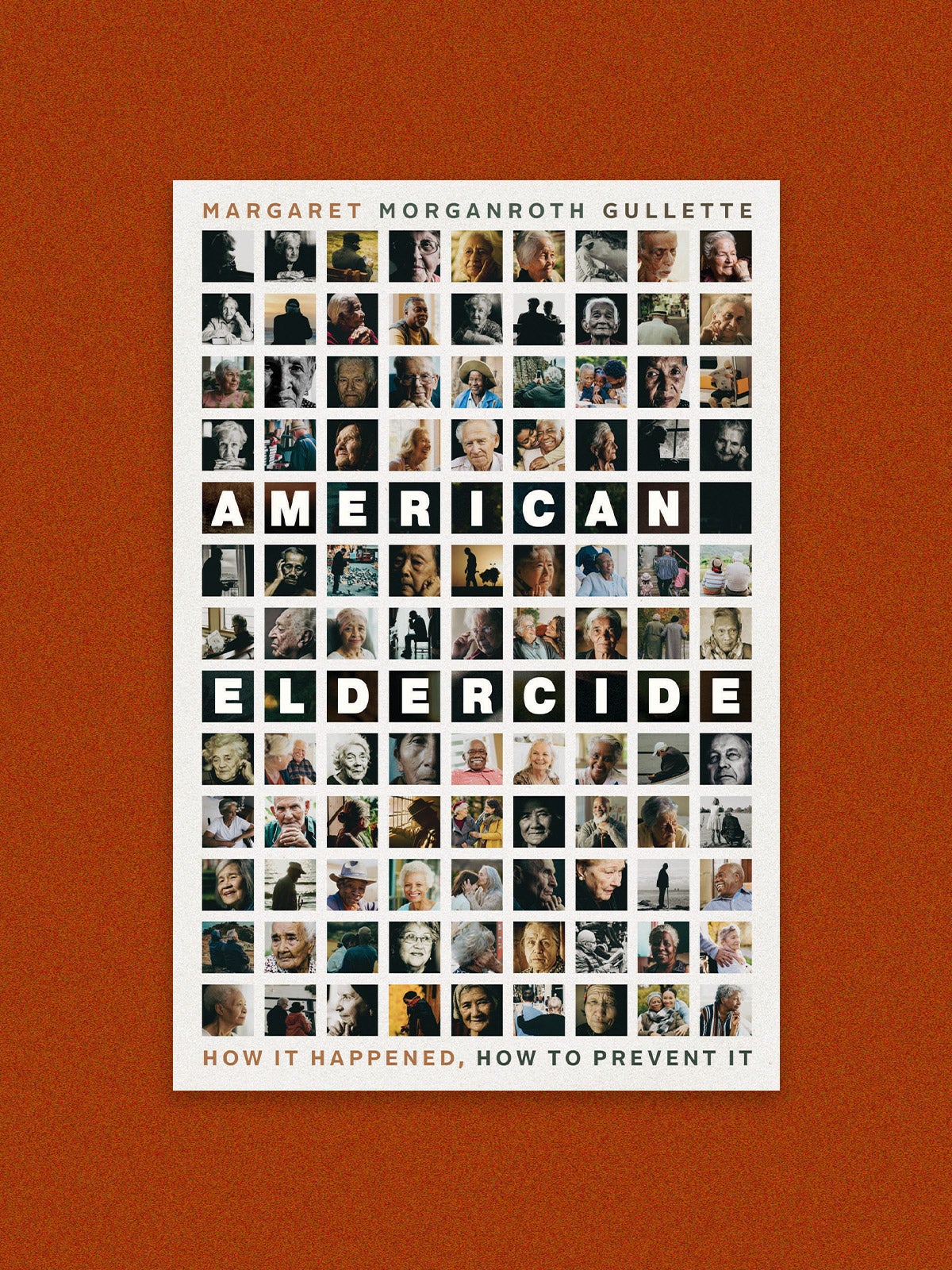

Book

The culmination of a “silent eldercide going on for decades”

It is no secret that the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States was particularly dangerous to residents of nursing homes. The statistics are chilling: This group of about 1.4 million people comprises less than one percent of the U.S. population, but has accounted for as many as 20 percent of Covid fatalities.

Even given the high lethality of the disease among the old and medically compromised, many nursing home deaths could and should have been avoided—with better infection control, paid sick leave for employees, and other public health measures. This is the core message of Margaret Morganroth Gullette’s provocative but often frustrating book, American Eldercide: How It Happened, How to Prevent It. The title posits that something akin to mass murder took place in nursing facilities—an overstatement that embodies Gullette’s righteous anger at what she calls “the humiliating and lethal governmental abandonment of these people.”

Gullette, an anti-ageism pioneer and resident scholar at Brandeis University’s Women’s Studies Research Center is, above all, a cultural critic. In Eldercide, she blames the tragedy of runaway nursing home deaths on “[i]ndifference, rooted in preexisting ageism.” The problem was compounded, she writes, by other prejudices, including sexism, sizeism, ableism, racism, homophobia, classism, and “dementism, or dread of Alzheimer’s-like memory loss.”

This emphasis won’t surprise anyone who knows Gullette’s previous work, including her award-winning 2017 book Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People. Here, her primary aim seems to be to shock readers out of complacency. Although she proposes solutions to prevent a future catastrophe—a federal long-term care benefit, a new department of elder and disability affairs, and the nationalization of nursing homes—her modest public health points are embedded in an overstuffed, meandering cultural critique.

Gullette’s principal argument is that society simply decided that nursing home lives, in contrast to those of the younger and more able-bodied, were expendable. She decries the Covid debacle as an intensification of “a silent eldercide [that] had been going on for decades” in these facilities. She cites research that a “pattern of understaffing for profit led to abuse or neglect and thus extra deaths.” But the evidence previously was sparse. The blizzard of deaths from Covid made the shortcomings of nursing homes impossible to ignore, she contends.

One might argue, and Gullette more or less does, that the real culprit is less deliberate criminality or malicious intent than the exigencies of capitalism, combined with ignorance and incompetence. Safety concerns notwithstanding, placing nursing home residents in private rooms would have cut into profits. Not only were the facilities understaffed; employees were low-paid and minimally trained. When vaccinations became available, many aides—in contrast to the residents themselves—refused them, with deadly results.

That the massive death toll was not inevitable is evidenced, Gullette suggests, by the existence of facilities that kept the pandemic largely at bay. Nonprofit homes, she notes, generally fared better than for-profit facilities. Gullette singles out one Baptist-run nonprofit in Baltimore that brought in personal protective equipment early and also had a full-time infection control specialist. Her pandemic wish list—probably all of ours—would have included more personal protective equipment, testing, contact tracing, and staffing.

An investigative account detailing more precisely what occurred in these settings, where lockdowns imposed extreme hardship without guaranteeing safety, would be an indispensable addition to the public health literature. That book remains to be written.

The specific differences between nursing homes that turned into death traps and others that did not would also offer valuable lessons for future pandemics and for public health in general. But Gullette wrestles unsuccessfully with the complexity of these issues. She bemoans the social isolation that bedeviled residents, a form of psychological torture, and, at the same time, seems to wish that it had been more thorough. She laments the death toll but also stresses repeatedly that many nursing home residents survived Covid. They are witnesses, but, so far, mostly silent ones. In lieu of tracking survivors down and doing her own interviews, Gullette complains that the media, besieged by the crisis and largely shut out of these facilities at the height of the pandemic, didn’t publish more first-person accounts.

Gullette’s writing style can be clear and punchy, if not always succinct. Early, graphic accounts of the pandemic, she suggests, confounded the nursing home residents with their residences: “Squalor became attached to the dying inhabitants as a group. The result was, I fear, a perverse appeal to a squeamish side that many of us possess. Lacking fuller context, this side is third cousin to bullying. It is first cousin to aversion. It is the bad brother of indifference.”

For better and sometimes worse, Gullette touches on a dizzying range of topics, from the imperatives of ventilator triage to grocery store senior hours and cultural representations of dementia. The narrative is powered by indignation. But it is also insistently nonlinear, unfocused, repetitive, and larded unhelpfully with quotes from the likes of Simone Weil, George Orwell, Hannah Arendt, Emily Dickinson, and Albert Camus.

The pandemic, Gullette writes, “was a superstitious time, filled with bad magical thinking.” Now she wants more testimony about that time, and a monument to one particular group that perished: the National Eldercide Memorial for Nursing-Facility Residents Who Died of COVID. That’s not a proposition any Congress is likely to embrace.

“Forgetting the residents is our problem as a nation,” Gullette concludes, with characteristic passion, “because the Eldercide goes on.” In her view, it is a “cultural deformity” that both preceded the pandemic and aggravated it, and now seems primed to outlast it.

Book cover: The University of Chicago Press